|

|

| Tuberc Respir Dis > Volume 78(4); 2015 > Article |

|

Abstract

Primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) of the lung is highly aggressive and quite rare. We report here a case of anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive endobronchial ALCL, that was initially thought to be primary lung cancer. A 68-year-old woman presented with hemoptysis, dyspnea, and upper respiratory symptoms persisting since 1 month. The hemoptysis and and bronchial obstruction lead to respiratory failure, prompting emergency radiotherapy and steroid treatment based on the probable diagnosis of lung cancer, although a biopsy did not confirm malignancy. Following treatment, her symptoms resolved completely. Chest computed tomography scan performed 8 months later showed increased and enlarged intra-abdominal lymph nodes, suggesting lymphoma. At that time, a lymph node biopsy was recommended, but the patient refused and was lost to follow up. Sixteen months later, the patient revisited the emergency department, complaining of persistent abdominal pain since several months. A laparoscopic intra-abdominal lymph node biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of ALCL.

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a lymphoma of the T- or null-cell linage, compromising approximately 2% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas1. It is classified into two groups according to its expression of the enzyme anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). ALK-positive ALCL has a more favorable prognosis and occurs predominantly in young, male patients compared with ALK-negative ALCL, which is associated with a worse prognosis and typically occurs in older patients1. ALCL has a tendency to involve extranodal sites, mostly the skin, soft tissue, bones1; however, primary ALCL of the lung is very rare1. We described a patient with an endobronchial mass at left proximal main bronchus extending to carina presenting as hemoptysis and hypoxemia which was diagnosed as ALK-positive endobronchial ALCL.

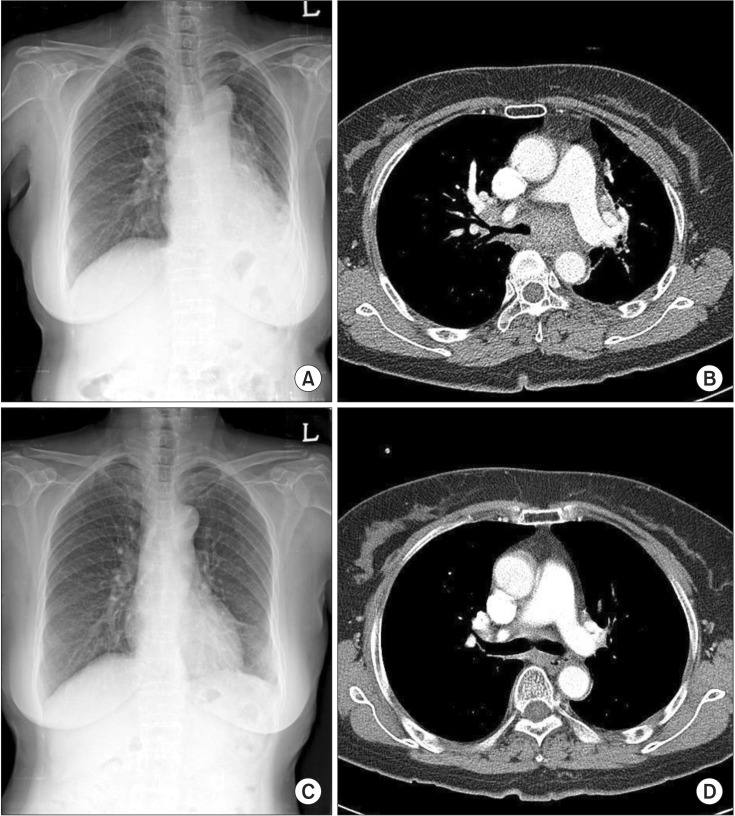

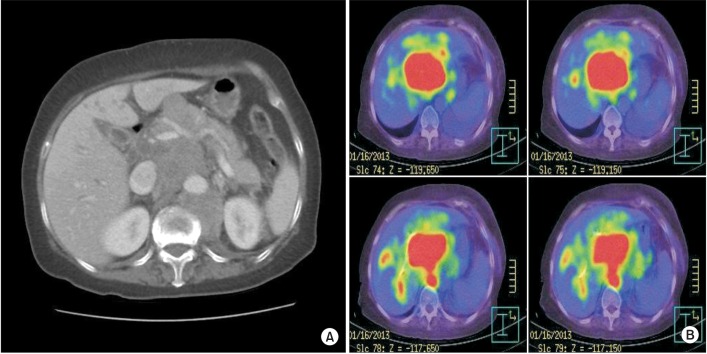

Five years ago, a 68-year-old woman presented with hemoptysis (approximately 60 mL), dyspnea, and upper respiratory symptoms that had persisted for 1 month. She had undergone a left thyroidectomy to remove thyroid cancer. A chest radiograph revealed a collapse of the left lower lung, probably caused by a left main bronchial obstruction. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the lung revealed obstruction of the left main bronchus accompanied by a large endobronchial mass (Figure 1A, B). The next day, a bronchoscopy identified showed total obstruction of the left main bronchus, with evidence of active bleeding and the bronchoscopic findings suggested bronchogenic carcinoma (Figure 2A), and positronemission tomography (PET)-CT identified a hypermetabolic endobronchial mass involving carina obstructing left main bronchus, highly suggestive of lung cancer. However, a histopathologic examination of the bronchoscopic biopsy revealed only ulceration with granulation tissue (Figure 3A). Hypoxemia and dyspnea worsened and hemoptysis aggravated; oxygen saturation was barely maintained between 88% and 90% by using an oxygen mask with a 15-L flow rate. Thus, emergency radiotherapy was administered based on the probable diagnosis of lung cancer as suggested by the chest CT, PET-CT, and bronchoscopic findings, even though the biopsy did not confirm malignancy. As a result of the radiotherapy, hypoxemia resolved, hemoptysis decreased, and the mass obstructing the bronchus diminished in size. Two days later, a second bronchoscopy detected no evidence of bleeding and resolution of all bronchial obstruction (Figure 2B). Two weeks after cessation of radiotherapy, a follow-up chest CT scan revealed that the size fo the endobronchial mass had markedly decreased and obstructive collapse had improved (Figure 1C, D). However, bronchoscopic rebiopsy was performed again after the hypoxemic respiratory failure resolved, but it identified only ulceration and granulation tissue. The patient was discharged after she had fully recovered from life-threatening respiratory failure. Because the patient was diagnosed with a probable malignancy, she continued to follow up in the clinic. A follow-up chest CT scan which performed 2 months after her discharge revealed complete resolution of the previously identified endobronchial mass. However, a chest CT taken 6 months later revealed the presence of increased and enlarged multiple intra-abdominal lymph nodes. We recommended a biopsy of the intra-abdominal lymph nodes, however, the patient refused the biopsy and was eventually lost to follow-up. Two years ago, she visited the emergency room again, with a complaint of abdominal pain that had persisted for several months. An abdominal-pelvic CT scan revealed extensive intra-abdominal lymph node metastasis that had markedly progressed compared to the previous with the last CT scan (Figure 4A). PET-CT also showed hypermetabolic intra-abdominal lymph nodes, highly suggestive of a malignancy such as lymphoma (Figure 4B). However, chest CT showed no evidence of malignancy. A diagnostic laparoscopic biopsy was performed on the omental and mesenteric lymph nodes revealed highly atypical large lymphoma cells with marked pleomorphism. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the tumor cells were positive for CD30, epithelial membrane angiten and ALK. And the patient was diagnosed with ALK-positive ALCL (Figure 3). She was administered chemotherapy consisting of cyclophosphamide and prednisone because her bilirubin levels were too high to receive the standard chemo-regimen in ALCL, a CHOP-regimen including cyclophosphamide, hydroxyl doxorubicin, oncovin, and prednisone. Following the first chemotherapy cycle, and abdominal-pelvic CT revealed a decrease in the size of the intra-abdominal lymph nodes. However, we could not evaluate the patient's response to chemotherapy or determine a final prognosis because the patient eventually died of biliary sepsis. It is possible that the previously undiagnosed lung mass was endobronchial ALCL that recurred in the lymph nodes of the intra-abdominal cavity because the time between the first symptoms and the follow-up chest CT showing enlarged intra-abdominal lymph nodes was only 8 months.

Primary pulmonary lymphoma (PPL) involves the pulmonary parenchyma and/or lymph nodes in the mediastinal or hilar areas. PPL is a rare neoplasm that accounts for 0.5%-1.0% of all malignant lymphomas occurring at lower rates in Hodgkin lymphoma than in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, for which it represents less than 1%2. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma involving the endobronchial tree and/or presenting as an endobronhical mass is rare3. Endobronchial involvement of ALCL specifically is extremely rare3. To the best of our knowledge, only 10 cases of endobronchial have been reported4,5,6. Four of which were in adults. Two cases were ALK-negative primary endobronchial ALCL, one case was ALK-positive endobronchial ALCL with systemic involvement, and one case was endobronchial ALCL with bone marrow involvement that was not tested immunohistochemically for ALK expression. Therefore, as far as we know, the present case is the first reported endobronchial ALK-positive ALCL without systemic involvement. It was very interesting in that the tumor mass in the present case initially manifested at the proximal left main bronchus extending carina as a single conglomerated central mass mimicking bronchogenic carcinoma without systemic involvement. Initially the patient in this case was considered to have small cell lung cancer with endobronchial obstruction based on imaging studies including CT findings. Therefore, a bronchoscopy was performed, but only necrotic tissue was obtained, despite performing a biopsy twice. Bronchoscopy is known to have a low diagnostic yield in patietns with pulmonary lymphoma, and therefore video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) or open lung biopsy is recommented7. This is supported by the fact that only one out of 11 primary pulmonary ALCL including pediatric cases was diagnosed on a bronchoscopic biopsy in the recent review8. In cases where a definite diagnosis by endoscopic biopsy is not attained, obtaining tissue from other sites by a different method should be considered. In the current case, different biopsy modalities such as endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration, VATS or open lung biopsy would have been viable alternative options. However, emergency radiotherapy was needed to save the patient's life, and we could not afford to wait for another chance of biopsy. After the patient recovered from respiratory failure a bronchoscopy and a re-biopsy of the remnant mass was performed, detecting only a necrotic tissue. It is possible that radiotherapy inhibited the acquisition of malignant cells. There are other treatment modalities in the management of malignant hemoptysis such as bronchoscopic intervention including bronchial stent insertion, bronchial aretery embolization, and surgery9. In this case, the mass that resulted in the patient's respiratory failure was not detected on the chest CT scan after emergency radiotherapy. The lymph nodes in the abdomen had increased in size, implicating lymphoma, after 8 months, which was the time interval between the first diagnosis of pulmonary malignancy and the diagnosis of ALK-positive ALCL in the abdomen. It is possible that the lesion, previously undiagnosed, was a result of inflammatory disease based on the histopathology. However, the lesion presented as a mass and disappeared completely disappeared after radiotherapy. Moreover, the findings on a chest CT and PET-CT scans supported the diagnosis of a malignant mass. Based on time interval between the first presentation of tumor and diagnosis of ALCL in the abdomen and the previous imaging and clinical features, a diagnosis of endobronchial ALCL with recurrence in the abdomen is more feasible than explaining double primary tumor. In conclusion, initially undiagnosed tumor in this case could be diagnosed as ALK-positive endobronchial lymphoma without systemic involvement. There is also another possibility that endobronchial lesion could be explained by endobronchial extension of lymph node. It could be helpful for clinicians to think about the possibility of primary pulomonary ALCL in front of the patient presenting with endobronchial mass obstructing airway and hemoptysis without concrete pathologic confirmation, which is very sensitive to radiotherapy despite the rarity of primary pulmonary ALCL, especially endobronchial ALCL.

References

1. Medeiros LJ, Elenitoba-Johnson KS. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;127:707-722. PMID: 17511113.

2. Kim JH, Lee SH, Park J, Kim HY, Lee SI, Park JO, et al. Primary pulmonary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004;34:510-514. PMID: 15466823.

3. Rush WL, Andriko JA, Taubenberger JK, Nelson AM, Abbondanzo SL, Travis WD, et al. Primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the lung: a clinicopathologic study of five patients. Mod Pathol 2000;13:1285-1292. PMID: 11144924.

4. Barthwal MS, Deoskar RB, Falleiro JJ, Singh P. Endobronchial non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2005;47:117-120. PMID: 15832956.

5. Xu X. ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma primarily involving the bronchus: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:460-463. PMID: 24427373.

6. Han SH, Maeng YH, Kim YS, Jo JM, Kwon JM, Kim WK, et al. Primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the lung presenting with acute atelectasis. Thorac Cancer 2014;5:78-81.

7. Ferraro P, Trastek VF, Adlakha H, Deschamps C, Allen MS, Pairolero PC. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:993-997. PMID: 10800781.

8. Yang HB, Li J, Shen T. Primary anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the lung. Report of two cases and literature review. Acta Haematol 2007;118:188-191. PMID: 17934256.

9. Lee SA, Kim DH, Jeon GS. Covered bronchial stent insertion to manage airway obstruction with hemoptysis caused by lung cancer. Korean J Radiol 2012;13:515-520. PMID: 22778577.

Figure┬Ā1

An initial chest X-ray (A) and chest computed tomography (B) revealed obstruction of the left main bronchus with obstructive collapse with air trapping in the left lung, which suggested lung cancer with obstructive collapse. Chest X-ray (C) and chest CT (D), taken on the 12th day after radiotherapy and steroid administration, revealed a markedly decreased mass and disappearance of obstruction in the left main bronchus.

Figure┬Ā2

Bronchoscopy showed total obstruction of the left main bronchus (A, arrow indicates the mass located at proximal left main bronchus extending carina). Bronchoscopy done after radiotherapy showed no evidence of bleeding and resolved obstruction (B, arrow indicates the remnant of mass).

Figure┬Ā3

The biopsy performed on her first hospitalization showed only ulceration and granulation tissue (A, H&E stain, ├Ś100). Laparoscopic biopsy from intra-abdominal lymph nodes shows anaplastic large cell lymphoma cells having marked pleomorphism (B, H&E stain, ├Ś400). Immunohistochemical stain reveals positivity for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (C, ├Ś400), epithelial membrane angiten (D, ├Ś400), and CD30 (E, ├Ś400).

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Effect of Bronchial Artery Embolization in the Treatment of Massive Hemoptysis1993 December;40(6)

A Case of Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Misdiagnosed as Pulmonary Tuberculosis.1998 February;45(1)

Effect of Bronchial Artery Embolization(BAE) in Management of Massive Hemoptysis.1999 January;46(1)

A Case of Bronchial Artery Aneurysm Presenting with Massive Hemoptysis.2002 January;52(1)

A case of endobronchial aspergilloma with massive hemoptysis.2004 December;57(6)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Print

Print Download Citation

Download Citation