Pneumatosis Intestinalis Complicated by Pneumoperitoneum in a Patient with Asthma

Article information

Abstract

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is a very rare condition that is defined as the presence of gas within the subserosal or submucosal layer of the bowel. PI has been described in association with a variety of conditions including gastrointestinal tract disorders, pulmonary diseases, connective tissue disorders, organ transplantation, leukemia, and various immunodeficiency states. We report a rare case of a 74-year-old woman who complained of dyspnea during the management of acute asthma exacerbation and developed PI; but, it improved without any treatment.

Introduction

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is defined as the presence of a cystic gas pocket formed within the submucosal layer or subserosal layer of the gastrointestinal tract. The primary type accounts for about 15% of the cases, and the secondary type is associated with other gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and collagen vascular diseases, organ transplantation, and immunodeficiency1,2. Most cases are asymptomatic, and fewer than 15% of the patients show symptoms such as abdominal distension, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. PI has diverse clinical outcomes ranging from benign, which does not require treatment, to a septic condition that can lead to death3.

PI associated with asthma is extremely rare and, to our knowledge, only three cases have been reported worldwide4,5,6. We present a case of a patient who was diagnosed with asthma and later developed PI, which was detected incidentally by follow-up X-ray. The patient had no symptoms and recovered without any treatment.

Case Report

A 74-year-old Korean woman visited our hospital with complaints of severe cough and dyspnea for two weeks. She had a previous history of pulmonary tuberculosis but had no other respiratory diseases including asthma. Before she visited our clinic, she had used a bronchodilator inhaler prescribed previously by another clinic. Her symptoms were relieved somewhat after the medication, but dyspnea began to worsen the day before her visit to our hospital.

On physical examination, her breathing sounds were coarse with wheezing in both lung fields. There was no abnormal finding on chest X-ray, but luminal narrowing with wall thickening in the right middle lobe was noted in chest computed tomography (CT). The patient was diagnosed as acute asthma exacerbation. Treatment with a short-acting β2-agonist, anticholinergic nebulizer, and systemic steroid (intravenous hydrocortisone 5 mg/kg for 5 days then tapered to 2.5 mg/kg) was started and was continued for 10 days. Under the assumption that a respiratory infection was the provoking factor for the acute exacerbation of asthma, the patient was given intravenous antibiotics. However, she continued to experience dyspnea, and the wheezing sound on auscultation did not improve. We performed bronchoscopy, which showed stenosis in the right middle lobe bronchus. On a pulmonary function test during admission, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) was 1.24 L (88%, of the predicted value), and the FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) was 66%. After bronchodilator administration, FEV1 was 1.14 L (81%, of predicted) and FEV1/FVC was 66%, which indicated no bronchodilator response. The IgE level was <20 IU/mL, and a skin-prick test revealed nonspecific findings. About 2 weeks of medical therapy, her symptoms had been relieved and no more wheezing sounds were heard on chest auscultation. Systemic steroid was tapered to oral prednisolone (0.25 mg/kg) after using 15 days of intravenous hydrocortisone.

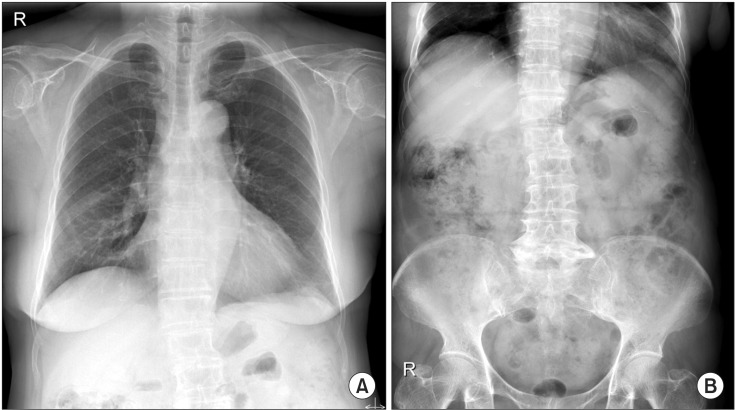

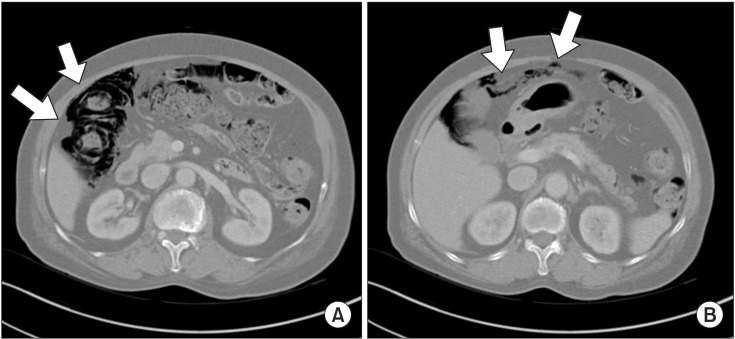

On the chest X-ray during a routine follow-up before discharge, pneumoperitoneum was newly noted (Figure 1A). Abdominal X-ray also showed pneumoperitoneum and retropneumoperitoneum (Figure 1B). Abdominal CT showed PI in the proximal ascending colon to distal transverse colon and a suspected rupture in the hepatic flexure (Figure 2A, B). The patient did not complain of any abdominal symptoms such as abdomen distension, vomiting, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Because she had no abdominal tenderness or rebound tenderness on physical examination, and no abnormal laboratory findings, she was discharged from the hospital without any treatment for PI. She was prescribed with oral prednisolone (0.25 mg/kg) and inhaled corticosteroid combined with a β2-agonist when discharge.

(A) Follow-up chest posterior-anterior plain radiograph taken at 14 days after admission shows pneumoperitoneum. (B) Abdominal left lateral decubitus radiograph shows pneumoperitoneum and retropneumoperitoneum.

(A) Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography shows pneumatosis intestinalis in the distal ascending colon and the proximal transverse colon (arrows). (B) Pneumoperitoneum probably caused by hepatic flexure perforation (arrows) was noted.

One week later, a chest X-ray, in the outpatient department showed no pneumoperitoneum, but an abdominal X-ray showed the remnants of PI (Figure 3A, B). She still had no symptoms, and we planned to monitor the patient closely. In a follow-up pulmonary function test performed 8 months later, FEV1 was 1.02 L (81%, of predicted) and FEV1/FVC was 68%. After bronchodilator administration, FEV1 was 1.25 L (99%, of predicted), indicating a positive bronchodilator response. The patient has been monitored at our outpatient clinic for 2 years, during which time she has been maintained with inhaled corticosteroid combined with a β2-agonist and she has been free of symptoms for PI.

Discussion

PI is defined as the presence of a cystic gas pocket formed within the submucosal layer or subserosal layer of the gastrointestinal tract. It is not a disease but a physical or radiological finding3. The primary type, which is not associated with other diseases, accounts for about 15% of the cases, and the secondary type accounts for the remaining 85% of the cases2. More than 58 diseases are associated with the secondary type including gastrointestinal, pulmonary, connective tissue, and hematological diseases1,6. The clinical manifestations and prognosis of PI are diverse and reflect those of the associated disease3.

The pathogenesis of PI is suggested to relate to the location of gas formation3,7. One hypothesized cause is migration of gas from gastrointestinal lumen into the submucosal or subserosal layer of the intestinal wall. Some conditions, such as vomiting and intestinal obstruction, can increase the intraluminal pressure, causing mechanical injury of the intestinal wall a break in the mucosa, which allow migration of gas. An immunosuppressed state, use of steroid, and cytotoxic drugs can make the intestinal wall susceptible to mechanical injury. A second hypothesis suggests that gas formed by bacteria in the gastrointestinal wall migrates into the intestinal wall, where they contribute to the formation of PI. A third hypothesis is that air leaked from an alveolar rupture travels to the retroperitoneum through mediastinal vessels and locates within the mesentery of the bowel. The latter is considered the least probable explanation because no case of air in the mesentery has been reported in a PI patient. In our patient, we assumed that the severe cough because of asthma attack caused an abrupt increase in the intraluminal pressure in the gastrointestinal tract and that the high-dose systemic steroid made the intestinal wall susceptible to mechanical injury, resulting in a break in the mucosa of the intestinal wall and PI. The fact that pneumoperitoneum and PI regressed after tapering systemic steroid supports the relationship between development of PI and steroid use. Three cases of PI in asthma patients have been reported. In one case, a 47-year-old man with severe status asthmaticus developed PI4. It was suggested that PI was initiated by rupture of a pulmonary bleb and mediastinal dissection of the gas. He complained of gastric distention, and became completely asymptomatic after conservative care. In the second case, a 19-year-old patient with PI associated with severe acute asthma was admitted to the intensive care unit5. Bowel infarction was shown by abdominal X-ray, and the patient underwent exploration and a double ileostomy. In the third case, a 25-year-old woman with asthma developed PI after high-dose prednisolone6. She reported chronic abdominal pain, but her symptom resolved after tapering of the prednisolone. This latter case suggested an association between steroid use and the development of PI.

The most frequent symptoms of PI are diarrhea, hematochezia, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, constipation, weight loss, and tenesmus, but many patients are asymptomatic, as was our patient8,9. In most cases, no abnormal findings are found on physical examination, and abdominal distension or hepatomegaly sometimes appears10. The radiologic appearance of PI does not reflect the symptoms and severity of PI11,12. With regard to complications, 3% of PI patients have pneumoperitoneum, volvulus, hemorrhage, or perforation9. In the current patient, abdominal CT showed pneumoperitoneum, but there were no significant symptoms or abnormal findings on physical examination. The pneumoperitoneum resolved spontaneously without any specific treatment.

Simple X-ray, abdominal sonography, lower gastrointestinal enterography, CT, and colonoscopy are common diagnostic tools1. The appearance of translucent shadow parallel to the gastrointestinal wall is a major X-ray finding. Abdominal sonography reveals hyperechoic lesions within the intestinal wall. Gastrointestinal fluoroscopy can easily visualize the border of the gas pocket. The most accurate diagnostic tool is abdominal CT, which shows that gas pocket is located alongside the intestinal wall, consistent with PI. Colonoscopy should be performed only when PI is strongly suspected, and the diagnosis is confirmed when the bulging lesion containing the gas pocket is deflated after being artificially punctured.

For at least 50% of the patients, PI is absorbed spontaneously, and asymptomatic PI patients do not require treatment9. In cases of serious gastrointestinal symptoms, a few days of an elementary diet, antibiotics, or high-concentration oxygen supply with a Venturi mask or hyperbaric oxygen assist recovery, but low-concentration oxygen is also clinically beneficial1,13. Based on the hypothesis that anaerobic bacteria are the source of gas production, antibiotic therapy usually includes metronidazole, tetracycline, ampicillin, and vancomycin. Short-term antibiotic therapy reduces the risk of recurrence, and it is recommended that antibiotics is continued for 2 months8. When pneumoperitoneum is accompanied with PI, surgery is not usually required if there is no severe gastrointestinal symptom or surgical indication14,15. For patients who do not respond to medical therapy or who develop complication such as intestinal obstruction, surgical option is considered3. In our patient, as she had no symptoms and significant signs for PI with pneumoperitoneum, she was discharged without any treatment for PI. Follow-up abdomen X-ray one week later showed complete disappearance of pneumoperitoneum, although a series of follow-up X-rays showed remnants of PI.

In conclusion, although incidence of PI is not high and clinical outcome of it is frequently not severe, clinicians should be aware of the potential development of PI in asthma patients. Appropriate medical or surgical intervention may be needed according to the severity of the PI.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.