The Association between Mortality and the Oxygen Saturation and Fraction of Inhaled Oxygen in Patients Requiring Oxygen Therapy due to COVID-19–Associated Pneumonia

Article information

Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) can manifest in a range of symptoms, including both asymptomatic systems which appear nearly non-existent to the patient, all the way to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Specifically, COVID-19–associated pneumonia develops into ARDS due to the rapid progression of hypoxia, and although arterial blood gas analysis can assist in halting this deterioration, the current environment provided by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to an overall lack of medical resources or equipment, has made it difficult to administer such tests in a widespread manner. As a result, this study was conducted in order to determine whether the levels of oxygen saturation (SpO2) and the fraction of inhaled oxygen (FiO2) (SF ratio) can also serve as predictors of ARDS and the patient’s risk of mortality.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study conducted from February 2020 to Mary 2020, with the study’s subjects consisting of COVID-19 pneumonia patients who had reached a state of deterioration that required the use of oxygen therapy. Of the 100 COVID-19 pneumonia cases, we compared 59 pneumonia patients who required oxygen therapy, divided into ARDS and non-ARDS pneumonia patients who required oxygen, and then investigated the different factors which affected their mortality.

Results

At the time of admission, the ratios of SpO2, FiO2, and SF for the ARDS group differed significantly from those of the non-ARDS pneumonia support group who required oxygen (p<0.001). With respect to the predicting of the occurrence of ARDS, the SF ratio on admission and the SF ratio at exacerbation had an area under the curve which measured to be around 85.7% and 88.8% (p<0.001). Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified that the SF ratio at exacerbation (hazard ratio [HR], 0.916; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.846–0.991; p=0.029) and National Early Warning Score (NEWS) (HR, 1.277; 95% CI, 1.010–1.615; p=0.041) were significant predictors of mortality.

Conclusion

The SF ratio on admission and the SF ratio at exacerbation were strong predictors of the occurrence of ARDS, and the SF ratio at exacerbation and NEWS held a significant effect on mortality.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, has spread rapidly around the world. Daegu in Korea was the center of an outbreak in which the number of affected patients increased rapidly since the first community case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported on February 18, 20201.

COVID-19 presents with a variety of clinical patterns, ranging from asymptomatic through mild to severe respiratory disease; approximately 5% of patients develop respiratory failure and require intensive care2,3. Mortality for those with COVID-19–associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is 61.5%4, whereas mortality for those on ventilator treatment is 65.7%–94%, which is higher than that due to other causes5. COVID-19 can lead to ARDS or rapid progression of hypoxemia, which worsens the patient’s condition and prognosis3. Therefore, it is important to identify and recognize risk factors for ARDS in patients who are deteriorating rapidly.

Currently, ARDS is defined as a partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2)/fraction of inhaled oxygen (FiO2) (PF ratio) of 300 or less, as measured by arterial blood gas analysis (ABGA)6. But a study7 shows that, when diagnosing conventional ARDS, oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2/FiO2) (SF ratio) instead of arterial blood gases is related to the PF ratio. COVID-19–associated ARDS is similar to common ARDS, but there are differences8,9. To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined whether the SF ratio is applicable to COVID-19–associated ARDS.

Therefore, this study was conducted to determine whether oxygen saturation is an important predictor of ARDS in those with COVID-19–associated pneumonia requiring oxygen therapy, and whether the SF ratio predicts development of ARDS and subsequent mortality. This retrospective analysis examined differences in clinical outcomes between hospitalized COVID-19 patients with ARDS and non-ARDS pneumonia, and examined the association between the SF ratio, onset of ARDS, and mortality.

Materials and Methods

1. Study design and definition of terms

This study was a single-center retrospective cohort study that enrolled patients with COVID-19–associated pneumonia who were hospitalized and treated at Daegu Catholic University Medical Center, Daegu, South Korea. The medical records of patients who were confirmed as positive of SARS-CoV-2 by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of nasopharyngeal swab or sputum samples from February 2020 to May 2020 were analyzed retrospectively. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Daegu Catholic University Medical Center (IRB No. CR-20-178). The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design.

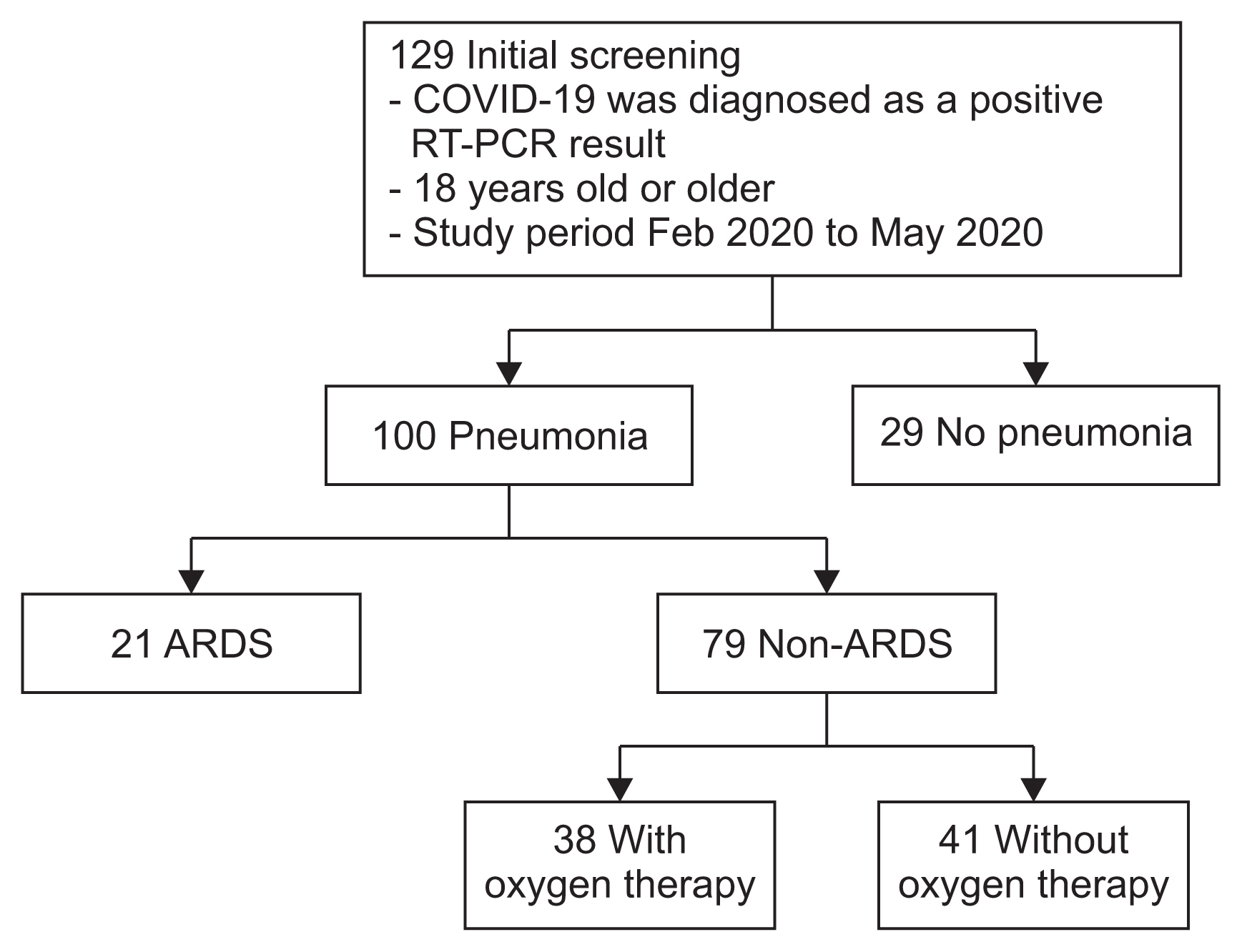

Inclusion criteria were as follows: COVID-19–associated pneumonia identified on chest imaging (chest X-ray or computed tomography [CT]); hospital admission; requirement for oxygen; and age >18 years. The exclusion criteria were lack of apparent pneumonia on chest imaging and no requirement for oxygen (Figure 1).

Flow chart for this study. A total of 129 patients aged ≥18 years were diagnosed as COVID-19–positive through reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Among them, 100 cases (77.5%) had COVID-19–associated pneumonia. Of all of these cases, 21 cases (16.3%) had ARDS, and 79 (61.2%) had non-ARDS pneumonia. Among the 79 cases of non-ARDS pneumonia, 38 (29.5%) required oxygen support. Data from the 21 cases in the ARDS group and the 38 cases in the non-ARDS oxygen-requiring support group were compared. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; RT-PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The ARDS group was defined as follows according to Berlin’s definition6: a PF ratio of ≤300 at any time during hospitalization (although positive end-expiratory pressure was not measured at the time of diagnosis in this study); bilateral pulmonary infiltration; and no pulmonary edema or cardiogenic cause. The non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group was defined as requiring oxygen but not meeting the ARDS diagnostic criteria, although there was evidence of pneumonia on chest imaging. Length of hospital stay was defined as the interval from the date of hospitalization to the date of death, discharge or end of this study.

The oxygen delivery device, FiO2, and SpO2 were recorded. If the patient was receiving oxygen through a nasal cannula, the FiO2 value was calculated as 0.24 for 1 L/min, 0.28 for 2 L/min, 0.32 for 3 L/min, 0.36 for 4 L/min, and 0.4 for 5 L/min. If the patient wore a simple oxygen mask, the FiO2 value was calculated as 0.4 for 5–6 L/min. If the patient was receiving more than 10 L/min of oxygen with a mask with reservoir bag, the FiO2 value was calculated as 0.810. If the patient used the high flow nasal cannula (HFNC), the measured FiO2 on the machine was recorded. When measuring SpO2 to increase the accuracy of SpO2, check the sensor’s optimal position, cleanliness, and satisfactory waveform, and there is no position change or suction for at least 10 minutes before measurement. There is no invasive procedure for at least 10 minutes prior to measurement11. SpO2 was observed for a minimum of 1 minute before the value was recorded7.

Clinical characteristics, vital signs, SpO2, FiO2, PaO2, the SF ratio, the PF ratio, and laboratory results (including ABGA), length of hospital stay, and mortality were compared between the ARDS group and non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group. The optimal cut-off value for the SF ratio for predicting ARDS occurrence was determined based on the threshold yielding the best combination of sensitivity and specificity using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis.

The data were used to ascertain whether the SF ratio can predict ARDS and whether a cut-off value can predict mortality.

2. Clinical data assessment and management

Initially, SpO2 “on admission” was measured for all patients, and the “SF ratio on admission” was calculated. ABGA was used selectively for patients in poor condition or showing a clear reduction in oxygen saturation. A “PF ratio on admission” was calculated for these patients. The point at which the highest oxygen concentration was required is defined as “at exacerbation.” In the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen group, 18 cases only maintained the oxygen concentration they first applied, and 20 cases had to increase oxygen as the oxygen demand increased. In 20 cases of the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen group, there was no need to raise oxygen any more after raising the oxygen concentration to the maximum, and this was defined as the point of exacerbation. In the ARDS group, oxygen levels generally peaked before intubation, and the point at which the highest oxygen concentration was applied before intubation was defined as the point of exacerbation. In addition, performing ABGA or measuring SpO2 at the point of worsening allowed calculation of the “PF ratio at exacerbation” and “SF ratio at exacerbation.”

Chest X-ray was performed for all hospitalized COVID-19 patients; chest CT scans were obtained for 120 of 129 cases (93%). Oxygen saturation of all COVID-19–associated pneumonia patients was monitored; when saturation fell below 90%, oxygen was administered. At this time, ABGA was not always performed. FiO2 was increased to keep saturation above 90%. Based on oxygen saturation monitoring, low flow nasal oxygen therapy was changed to high flow nasal oxygen when necessary, and ventilator support was provided if saturation fell further.

Laboratory tests, vital signs, and the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) were measured on admission. NEWS12 is based on vital signs such as respiratory rate (RR), oxygen saturation, requirement for oxygen, body temperature (BT), systolic blood pressure (BP), heart rate, and mental status. The time taken to a positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 virus to become negative was also noted. All patients were treated empirically with antiviral therapy and antibiotics at the discretion of each physician.

3. Statistical analysis

Results are presented as absolute values and percentages. Continuous variables were not normally distributed; therefore, data are presented as the median and interquartile range (interquartile range). The Mann-Whitney U-test and Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to compare continuous and categorical data, respectively, between patients in the ARDS group and the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group. ROC curve analysis was used to determine the optimal cut-off value for the SF ratio (on admission and at exacerbation) for predicting ARDS occurrence; this was based on the threshold yielding the best combination of sensitivity and specificity. When identifying risk factors, univariate and multivariable Cox regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test (analysis was based on the SF ratio on admission and at exacerbation). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Overall, 129 patients were diagnosed as COVID-19–positive by SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR. Of these, 100 (77.5%) had COVID-19–associated pneumonia confirmed by chest X-ray or CT. The ARDS group comprised 21 cases (16.3%), and the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support comprised 38 cases (29.5%) (Figure 1).

1. Onset of ARDS

There was no difference in age, sex comorbidities, smoking status, BP, heart rate, RR, and BT between the two groups. However, at the time of admission, the NEWS score for the groups differed significantly: it was higher in the ARDS group than in the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group (p<0.001). Laboratory tests revealed significant differences in segmented neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), sodium, and procalcitonin levels between the two groups. The number of deaths in the ARDS group was 11 (52.4%), which was significantly higher than that in the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group (p<0.001). Significantly more patients in the ARDS group required invasive mechanical ventilator use, HFNC, steroids (p<0.001), and hydroxychloroquine (p=0.006). There was no difference between the two groups with respect to the time taken from symptom onset to the first negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 virus. There was no difference between the groups with respect to length of stay (Table 1).

Baseline, clinical, and laboratory characteristics, along with prescribed treatment for patients who had coronavirus disease 2019-related pneumonia and required oxygen therapy

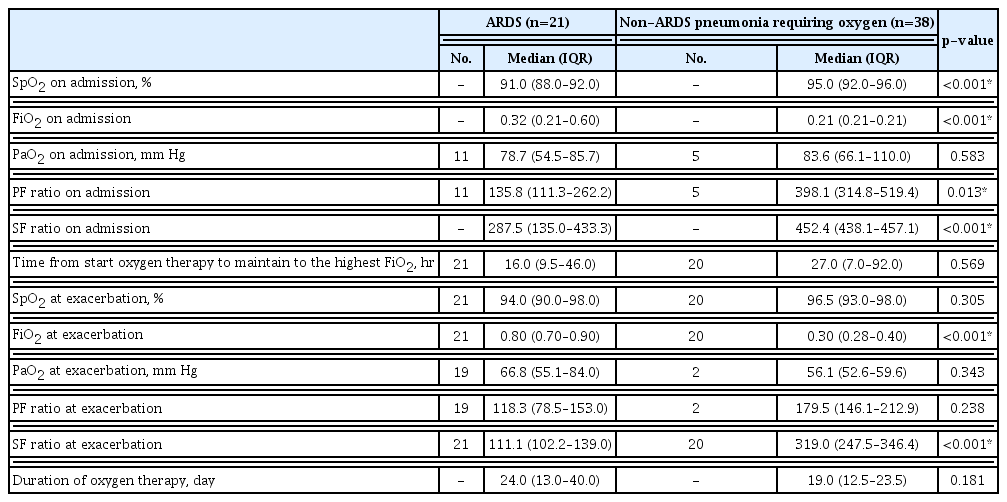

At the time of admission, the SpO2, FiO2, and SF ratios of the ARDS group were significantly different from those of the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group (p<0.001). At the time of admission, few patients underwent ABGA (11 out of 21 patients in the ARDS group [52.4%] and five out of 38 patients in the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group [13.2%]). Although there were few cases, the PF ratio for the 11 patients in the ARDS group was significantly different from that in the five patients in the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group (p=0.013). The time taken from the start of oxygen administration to the point at which the highest oxygen level was used was 16 hours for the ARDS group and 27 hours for the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group (p=0.569).

However, of the 38 patients in the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group, 18 (47.4%) maintained the initial FiO2 because there was no deterioration after initial oxygen administration; these patients were stable until discharge. When comparing the non-ARDS requiring oxygen group excluding those 18 cases and the ARDS group, SpO2 at exacerbation did not differ between the two groups (p=0.305), but FiO2 at exacerbation was significantly higher in the ARDS group (p<0.001). At exacerbation, only two out of 38 patients (5.3%) in the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group underwent ABGA; thus, there was no significant difference in the PF ratio at exacerbation between the two groups (p=0.238). However, the SF ratio at exacerbation was calculated for patients, and there was a significant difference between the two groups (p<0.001). There was no difference in the duration of oxygen therapy between the two groups (Table 2).

Oxygen-related outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019–associated pneumonia and who required oxygen therapy

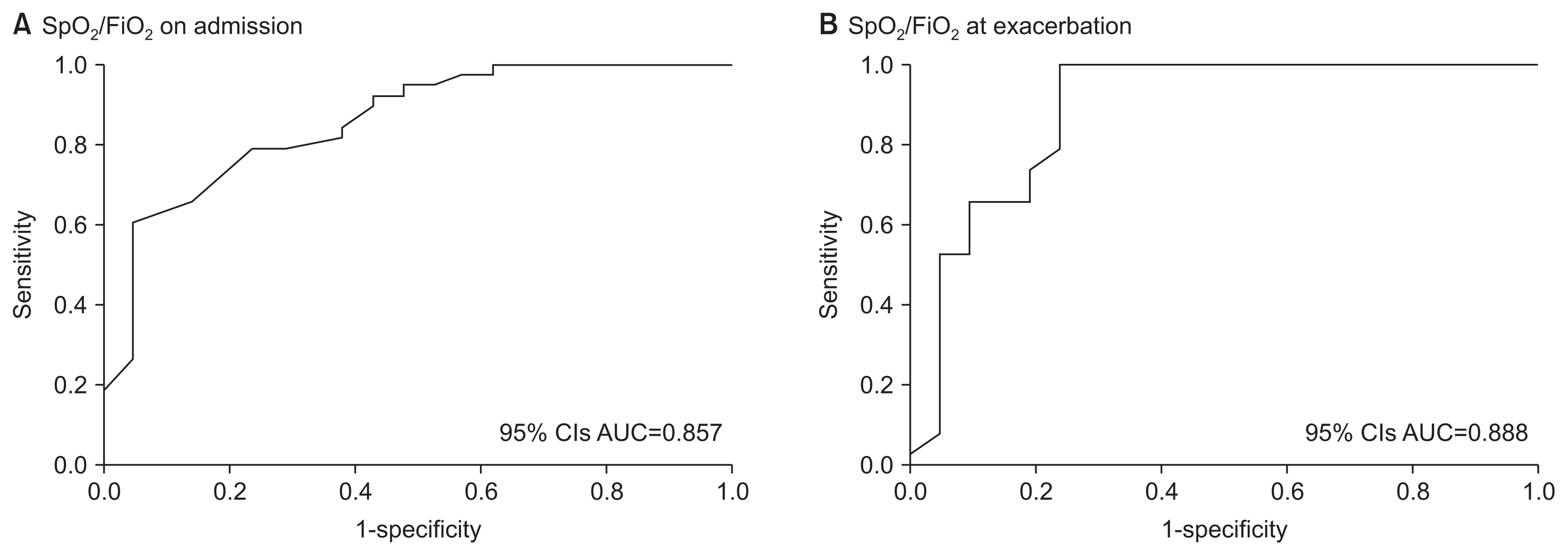

With respect to predicting occurrence of ARDS, the SF ratio on admission and the SF ratio at exacerbation showed an overall area under the curve of 85.7% and 88.8% (p<0.001) (Figure 2). ROC curve analysis showed that the optimal SF ratio on admission had a cutoff of 445 for predicting ARDS, demonstrating 60.5% sensitivity and 95.2% specificity. A previous study7 suggested an SF ratio ≤315 as a criterion that closely resembles the PF ratio of ≤300, which is the diagnostic criterion for ARDS. When we used this cut-off point as the standard, the ARDS diagnostic sensitivity was 92.1% and the specificity was 52.4%. The optimal SF ratio at exacerbation had a cut-off of 179 for predicting ARDS, demonstrating 99.9% sensitivity and 76.2% specificity.

Receiver operating characteristic curve of the SpO2/FiO2 ratio on admission (A) and the SpO2/FiO2 ratio at exacerbation for predicting the onset of acute respiratory distress syndrome (B) in 59 patients with coronavirus disease 2019-associated pneumonia. The areas under the curves are 85.7% (A) and 88.8% (B) (p<0.001). SpO2: oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry; FiO2: fraction of inhaled oxygen; CI: confidence interval; AUC: area under the curve.

2. Mortality

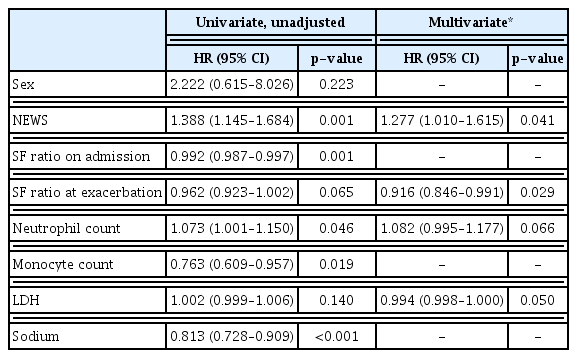

When comparing survivors and non-survivors, sex, NEWS, SF ratio on admission, SF ratio at exacerbation, neutrophil count, monocyte count, LDH and sodium was identified as significantly different variables for survival (data not shown). When examining risk factors for mortality in patients with COVID-19–associated pneumonia, univariate logistic regression identified sex, NEWS, SF ratio on admission, SF ratio at exacerbation, LDH, and sodium as significant. Multivariable logistic regression using these variables identified only the SF ratio at exacerbation as a significant predictor of mortality (odds ratio, 0.966; 95% CI, 0.943–0.990; p=0.006).

Univariate Cox regression analysis to identify risk factors contributing to mortality in patients with COVID-19–associated pneumonia requiring oxygen support, NEWS, SF ratio on admission, segmented neutrophil count, monocyte count, and sodium level were significant. Multivariate Cox regression analysis identified the SF ratio at exacerbation (HR, 0.916; 95% CI, 0.846–0.991; p=0.029) and NEWS (HR, 1.277; 95% CI, 1.010–1.615; p=0.041) as significant predictors of mortality (Table 3).

Risk factors presented as hazard ratios for the mortality rate for 59 patients with coronavirus disease 2019–associated pneumonia

Kaplan-Meier curves based on the SF ratio at exacerbation revealed that an SF ratio at exacerbation ≤179 was associated with significantly lower survival rate than an SF ratio >179 (log-rank test, p≤0.001) (Figure 3). In the group with an SF ratio at exacerbation ≤179, five survived (31.3%) and 11 died (68.8%), but in the group with an SF ratio >179, 43 survived (100%) and none died (p<0.001). When the SF ratio on admission was categorized using a cut-off value of 315, this had a significant effect on mortality as assessed by Cox regression analysis (HR, 11.700; 95% CI, 2.356–58.096; p=0.003).

Discussion

Progression of COVID-19–associated pneumonia to ARDS is dangerous and associated with increased mortality4. Therefore, it is important to manage patients quickly if they show signs of progressing to ARDS. However, diagnosing ARDS using ABGA is difficult due to the risk of infection of medical staff, and lack of manpower and resources. Here, we show that the SF ratio (calculated by oxygen saturation monitoring) can predict ARDS in those with COVID-19–associated pneumonia requiring oxygen.

The aim of the study was to identify onset of COVID-19–associated ARDS in the real world, thereby enabling more rapid treatment. Even when patients required the highest oxygen demand, only two of 38 (5.3%) in the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group underwent ABGA. However, the SF ratio on admission and at exacerbation could be measured for all patients, and the SF ratio predicted occurrence of ARDS at the time of admission or at the time of exacerbation. SF ratios and oxygen saturation monitoring are readily available at the bedside, and may facilitate appropriate and rapid triage of patients with COVID-19 to a higher level of care3. Thus, resources are conserved, and preventive and management measures are initiated more expeditiously3.

A diagnosis of ARDS is based on a PF ratio ≤300 according to the Berlin definition6. However, a recent large multinational study using the PF ratio found that clinicians failed to recognize ARDS in 40% of patients, and recognized it in only one in three patients when the ARDS criteria were first met13. Therefore, studies7,13–15 have examined whether the PF ratio can be replaced by the SF ratio, or whether the two values correlate. Rice et al.7 stated that SF ratios correlate with PF ratios, and that SF ratios of 315 are correlate with PF ratios of 300, which is the cut-off value of ARDS diagnosis. These criteria have been cited by other researchers16. Here, ROC analysis showed that the SF ratio on admission and SF ratio at exacerbation were good predictors of ARDS onset. In addition, Cox regression analysis showed that the SF ratio at exacerbation had a significant effect on mortality. If the oxygen is well maintained and SpO2 is high, SpO2 will not make a big difference even if the PaO2 difference is large17. In this case, the values of SF ratio have no clinical significance and there will be errors. All the papers that show good correlation between the SF ratio and the PF ratio so far have been based on ARDS or acute lung injury7,14, and this is thought to be the reason.

Cox regression analysis also showed that the NEWS on admission had a significant effect on mortality. The NEWS is a scoring system that helps quickly detect clinical deterioration in COVID-19 patients18. It is believed that NEWS on admission can accurately predict clinical deterioration and critical outcomes19. In particular, in COVID-19 infection, oxygen desaturation among NEWS are thought to have played an important role20. Among the NEWS in this study, the values significantly different between survivors and non-survivors were RR and SpO2 (p=0.018 and p=0.045, respectively).

Kaplan-Meier analysis based on an SF ratio at exacerbation cut-off point of 179 showed that the in-hospital survival rate of the ≤179 group was significantly lower than that of the >179 group (log-rank test, p<0.001) (Figure 3). Xie et al.21 reported that a SpO2 ≤90% was a strong predictor of mortality after oxygenation in cases of respiratory distress. That study predicted mortality based on subjective symptoms of dyspnea and SpO2 of 90% after oxygen administration, which did not reflect FiO2. These patients showed reduced SpO2, even with an increase in FiO2, so their condition would have been more serious. Going one step further, we investigated whether the SF ratio, a marker reflecting FiO2, can predict mortality in a meaningful way. We found no significant difference in SpO2 at exacerbation between the ARDS group and the non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group (Table 2) because FiO2 increased to maintain SpO2. Therefore, the SF ratio is an index that reflects the patient’s condition better than SpO2 alone. A decrease in the SF ratio appears to be an important predictor of mortality.

Also of interest, the level of sodium in ARDS group is significantly lower than that of non-ARDS pneumonia requiring oxygen support group (p=0.001). A systematic review, meta-analysis and retrospective cohort study shows that serum sodium concentration in severe or critical COVID-19 patients was significantly lower than those in mild and moderate patients22. This study explains that this phenomenon is probably due to the physiologic state of the body before viral infection. This condition may result in angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 overexpression and increase the risk and severity of COVID-19.

The study has several limitations. In nasal cannula, mask oxygen therapy, and even HFNC, FiO2 could change when room air oxygen was mixed depending on the patient’s breathing effort. The definition of “at exacerbation” was the point at which the highest oxygen concentration was used, which may be subjective and may be selection bias and misleading. We were not able to calculate the correlation between the PF ratio and the SF ratio because the PF ratio could not be confirmed in a large number of patients. In addition, this was a single-center study retrospective study; thus, the data may not be generalizable, and the study may suffer from selection bias.

In conclusion, the SF ratio on admission and the SF ratio at exacerbation predict occurrence of ARDS. The SF ratio at exacerbation has a significant effect on mortality. Therefore, a reduction of the SF ratio has important implications with respect to changes in a patient’s condition and is an important factor for predicting ARDS occurrence and mortality.

Notes

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: Kim EJ. Methodology: Kim EJ, Hong HL. Formal analysis: Kim EJ. Data curation: Kim EJ, Choi KJ. Software: Kim EJ. Validation: Hong HL. Investigation: Choi KJ, Kim EJ. Visualization: Kim EJ, Choi KJ. Writing - original draft preparation: Kim EJ. Writing - review and editing: Choi KJ, Hong HL, Kim EJ. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

No funding to declare.