Interstitial Lung Disease in a Patient with Dyskeratosis Congenita

Article information

Abstract

Dyskeratosis congenita is a rare congenital disorder characterized by a triad of reticular pigmentation of the skin, dystrophic nails, and leukoplakia of the mucous membrane. Sometimes it is associated with bone marrow failure, secondary malignancy and interstitial lung disease. Though it is rare, Dyskeratosis congenita is diagnosed relatively easily when clinicians suspect it. It can be diagnosed just by gross inspection with care. Dyskeratosis congenita should be considered as one cause associated with interstitial lung disease. In Korea, interstitial lung disease with dyskeratosis congenita has not been reported. We report a case and review the literature.

Introduction

Dyskeratosis congenita is a rare hereditary disorder characterized by dystrophic nails, abnormal skin pigmentation, and mucous leukoplakia. Non-mucocutaneous features include bone marrow failure, pulmonary fibrosis, and predisposing malignancy1. The prevalence of classic dyskeratosis congenita is approximately 1/1,000,000 individuals2. The primary causes of death in patients with dyskeratosis congenita are bone marrow failure and immunodeficiency (60-70%), pulmonary complications (10-15%), and malignancy (10%)3.

While dyskeratosis congenita has been reported in the Korean literature, to our knowledge, pulmonary involvement has not been mentioned4-8. Since pulmonary involvement is considered to be an important complication of dyskeratosis congenita, we report a case and review the literature.

Case Report

A 29-year-old Korean man who had smoked a fourth of a pack daily for twelve years, visited the hospital because of easy fatigue. His height was 172 cm and weight was 49 kg. He has never been exposed to occupational noxious gas like asbestos, chemical fumes, or organic dusts. He has taken no medications.

Recently, he suffered from dry cough and dyspnea on exertion. He felt easily exhausted but his weight or appetite was not changed. He denied febrile sensation or chills, and peripheral edema was not noted. His skin seemed mottled with pigmentation on the anterior chest and neck, but he didn't have photosensitivity or skin allergy. Also, leukoplakia was noted at his tongue and almost all of his finger and toe nails were markedly atrophic and dystrophic (Figure 1). However, we couldn't find joint swelling or deformity.

Mucocutaneous triad of abnormal skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, and leukoplakia. (A) Abnormal fine reticular pigmentation around the neck. (B) Leukoplakia on the tongue. (C, D) Markedly atrophic and dystrophic finger and toe nails.

Auscultation of the lungs revealed bilateral diffuse fine crackles without wheezes or rhonchi. The heart beat sounded regular without murmur. On the day of his visit, his blood pressure was 105/54 mm Hg, pulse rate was 79/min, respiratory rate was 17/min, and body temperature was 36.4℃.

He took a pulmonary function test and chest X-ray. The results showed that forced vital capacity (FVC) was decreased to 3.24 L (66% of predicted value), forced expiratory volume 1 second (FEV1) was 3.00 L (77% of predicted value). It showed a typical restrictive pulmonary disease pattern. Diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) was 37% of predicted value.

Chest X-ray revealed fibrostreaky and reticular attended infiltration in both lungs. His electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm. Hemoglobin was 12.4 g/dL and hematocrit was 36.3%. Anti-nuclear antibody and rheumatic factor were negative.

We began to review his hospital record and noticed that he has been admitted several times. When he was 17 years old, he had neurosurgery because of a traumatic subdural hematoma injury from a bicycle accident. At that time, thrombocytopenia was noted. During his hospital stay, he received a liver scan, bone marrow study, chromosomal analysis and other tests. His bone marrow biopsy revealed hypocellularity without dysplasia. He was not a candidate for bone marrow transplantation because marrow suppression was not that severe. Aplastic anemia without dysplasia was diagnosed throughout hematologic evaluation. Chromosomal analysis and intelligence quotient were normal. Viral marker showed no specific viral infection like parvovirus, hepatitis B or C that could cause pancytopenia. Liver scan showed splenomegaly with increased uptake at bone marrow.

During a previous admission period, the physician was curious about his unusual skin and dystrophied nails. The physician consulted regarding his skin lesion with a dermatologist. The dermatologist diagnosed his disease as dyskeratosis congenita.

His family includes two sisters who had no skin pigmentation or nail dystrophy. Only his mother's left second nail was dystrophied. He has two children, one son and one daughter. Presently they also have no symptoms of dyskeratosis congenita.

His disease was reported to The Korean Journal of Hematology5. He was the first case of dyskeratosis congenita with pancytopenia in Korea. But he didn't return after discharge because he had no further symptoms.

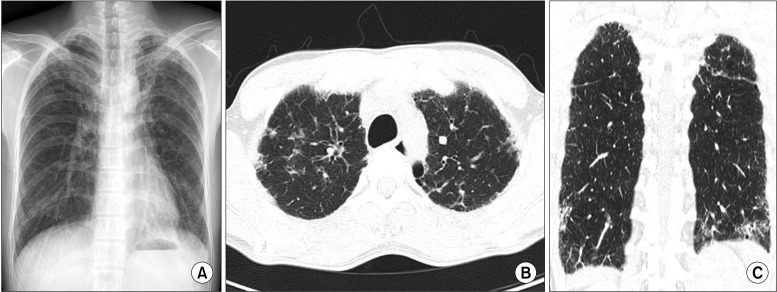

Ten years later, he visited the department of pulmonology because of easy fatigue with a tentative diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. But chest computed tomography (CT) showed an interstitial lung disease pattern (Figure 2). His symptoms and laboratory findings didn't support the possibility of autoimmune disorder. We diagnosed interstitial lung disease related to dyskeratosis congenita.

Chest X-ray and computed tomography taken on the first visit. (A) Fibrostreaky and reticular patterned infiltration at both lung fields. (B, C) Interstitial thickening along the subpleural area.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg but was admitted because of gastric ulcer bleeding. He has splenomegaly and thrombocytopenia, so bleeding risk was high. Prednisolone was stopped and he was followed up with supportive care. His symptom, dyspnea on exertion became aggravated. After 2 years, we reassessed his status by pulmonary function test and chest CT and found it had worsened. FVC was much declined to 2.57 L (52% of predicted value) and FEV1 was 2.32 L (59% of predicted value). The ratio FEV1 of FVC was 90%, but DLCO was 17%, DLCO/alveolar volume was 25%. Total lung capacity was 3.88 L (61% of predicted value). Chest CT showed progression of interstitial fibrosis but secondary malignancy evidence was not yet visible (Figure 3).

Discussion

Dyskeratosis congenita is characterized by a triad of dystrophied nails, skin pigmentation, and leukoplakia. It can be associated with pancytopenia, secondary malignancy, or interstitial lung disease as in this case. Genetic success was not confirmed, but it is suggested that X-linked recessive is important because of higher prevalence in men than in women9. There is a case report of successful stem cell transplantation with lung transplantation for dyskeratosis congenita10.

We didn't biopsy the lung tissue because of severe thrombocytopenia. But others report that dyskeratosis congenita is associated with usual interstitial lung disease pattern11. It is suggested that telomere abnormality or fibroblast is related to the disease12. In this case, the distribution of interstitial fibrosis is subpleural and affects the lower lungs rather than central and upper lungs. And there was no response of steroid treatment while interstitial fibrosis with traction bronchiectasi was progressed. These findings are the features of the usual interstitial pattern.

When interstitial lung disease is diagnosed the first time, it is important that doctors rule out the underlying causes provoking it. Dyskeratosis congenita is a rare disease, but it is diagnosed by simple inspection and related to secondary malignancy. So pulmonologists should be aware that dyskeratosis congenita is one of the causes of interstitial lung disease.

We experienced a patient who was diagnosed as dyskeratosis congenita with aplastic anemia, liver cirrhosis, and interstitial lung disease. It is the first case of dyskeratosis congenita with interstitial lung disease in Korea.