Introduction

Bronchoscopy has evolved over the past few decades and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) is widely used in clinical practice. Among EBUS techniques, radial probe (RP) EBUS-guided biopsy is commonly used to diagnose peripheral pulmonary lesions (PPLs) [

1].

This method offers high diagnostic yield and low complication rates for the diagnosis of PPLs. A meta-analysis that applied this method investigated 57 studies with a total of 7,872 PPLs and reported an overall weighted diagnostic yield of 70.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 68%-73.1%). The overall complication rate was 2.8% [

2]. A more recent meta-analysis updated these results and reported a pooled sensitivity of 0.72 and complication rate of 0.7%; sensitivity varied among institutions [

3]. The method of RP-EBUS-guided transbronchial lung biopsy (RP-EBUS-TBLB) varies significantly among institutions regarding the use of additional guidance tools such as a guide sheath (GS) or fluoroscopy [

2-

4].

The GS technique provides access to target bronchial lesions for repeated sampling and protecting against bleeding from the biopsy site by wedging the GS into the target lesion [

5]. The use of fluoroscopic guidance in addition to RP-EBUS can improve diagnostic yield while administering acceptable radiation doses to patients and clinicians [

6-

8]. However, fluoroscopy still exposes patients and practitioners to radiation, and consumes additional space, manpower, and costs (e.g., to install a shield room) [

9].

Few studies have explored the efficacy and safety of RP-EBUS-TBLB using a GS without fluoroscopy for PPLs [

10-

13]. Hence, in this study, we evaluated the diagnostic yield and complications of RP-EBUS-TBLB in diagnosing PPLs and identified factors associated with the diagnostic yield.

Materials and Methods

1. Study design and subjects

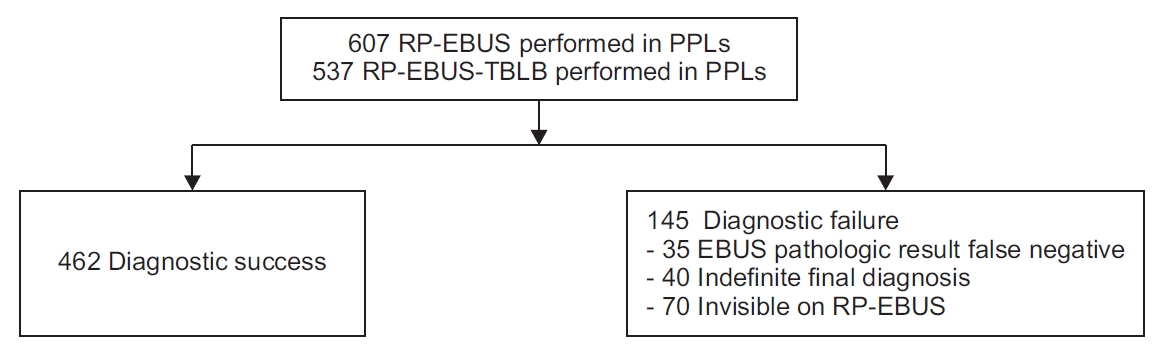

We performed a retrospective observational study on 607 consecutive patients who underwent RP-EBUS for PPLs from January 2019 to July 2020 at Yeungnam University Hospital (a 930-bed, university-affiliated, tertiary referral hospital in Daegu, South Korea). All EBUS-visualized lesions (n=537) were biopsied via RP-EBUS-TBLB (

Figure 1).

2. CT and bronchoscopy

All patients underwent thin-section chest computed tomography (CT) (0.75 mm slice thickness at intervals of 0.75 mm; SOMATOM Definition AS 64-slice CT system, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) less than seven days before RP-EBUS. Experienced pulmonologists reviewed the chest CT images before the procedure and planned a bronchial route to access the target lesion. The bronchus sign in CT was defined as the presence of a bronchus leading to the target lesion. The distance from the lesion to the pleura was measured as the shortest distance on an axial plane CT scan, as described previously [

14].

All bronchoscopy procedures were performed by three pulmonologists, each with more than 5 years of experience in respiratory medicine. Patients were sedated with 2.5-5.0 mg of intravenous midazolam and 25-50 ╬╝g fentanyl. A 4 mm bronchoscope (BF P260F, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to reach the bronchus closest to the target lesion. Then, a RP-EBUS (UM S20-17S, Olympus) was inserted inside a GS through the bronchoscope working channel. Following the discovery of the PPL, the RP was then removed, leaving the GS in place. Then, bronchial brush and biopsy forceps were introduced into the GS and brushings and biopsy specimens were collected. When TBLB was performed at our hospital, the lesion was identified with the RP, performed gain on the first three lung tissue samples, re-inserted the RP to ensure that the GS was not re-positioned in the lesion, and then performed an extra biopsy. X-ray fluoroscopy was not used.

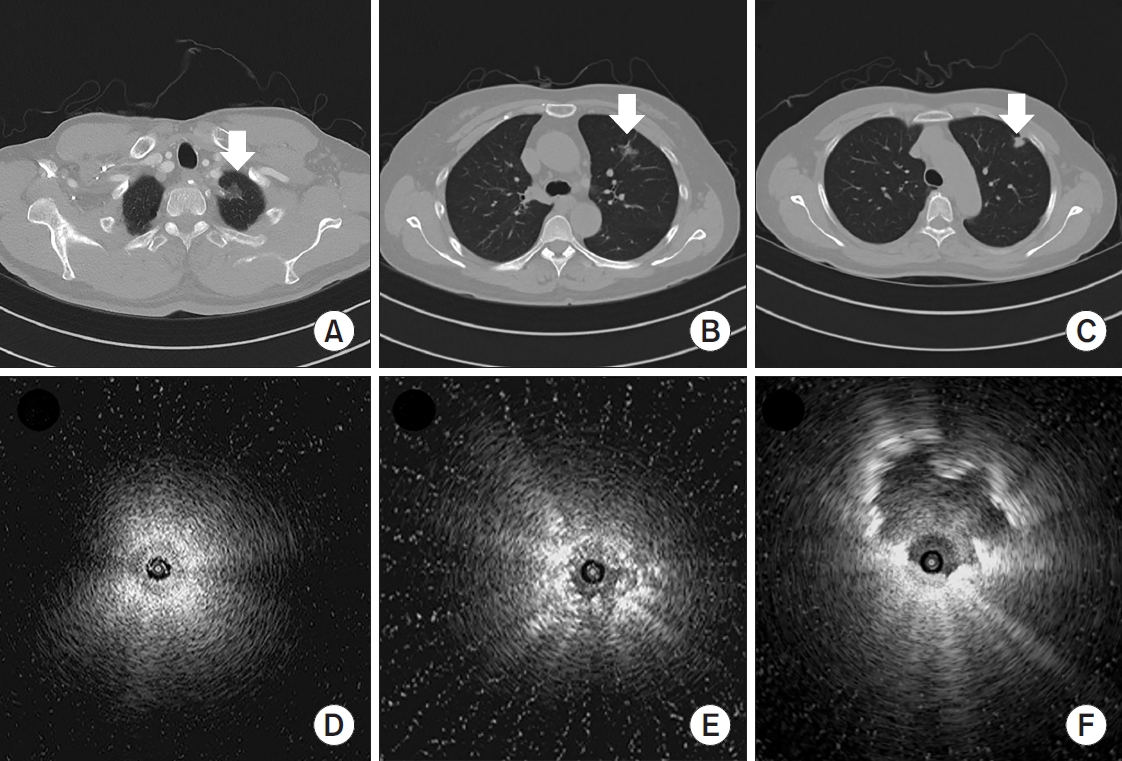

Figure 2 shows representative cases of RP-EBUS-TBLB with GS and without fluoroscopy in patients with suspected lung cancer.

3. Diagnostic classification

A final diagnosis of malignancy was made based on the definite histological evidence of malignancy, or clinical features consistent with malignancy. Benign lung lesion was diagnosed according to the following criteria: identification of definite benign features, regression of the lesion with medical treatment, and a stable size for at least 12 months. Lung lesion that was neither benign nor malignant was defined as indefinite. Lesions diagnosed as benign both at the beginning and at the end were considered as true-negative. Lesions initially diagnosed as benign but finally diagnosed with malignancy (EBUS pathologic result false-negative) were designated as false-negative. Indefinite final diagnosis and invisible on RP-EBUS cases were also considered as false-negative.

4. Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were compared to StudentŌĆÖs t test or the Mann-Whitney U test and were expressed as means┬▒standard deviations. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher exact tests and were described as frequencies (percentages). We calculated the diagnostic yield by dividing the number of diagnostic successes by the total number of cases. To explore factors that affected diagnostic yield, the study population was divided into two groups: a diagnostic success group (true-positive and true-negative results) and a diagnostic failure group (false-positive, and false-negative results). Univariable and multivariable (using the factors with p<0.1 in univariable analyses) logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors affecting the diagnostic yields. In all analyses, p<0.05 under a two-tailed test was considered as statistically significant. All statistical procedures were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

5. Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and its protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Yeungnam University Hospital (YUH IRB 2020-09-025). The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design.

Discussion

This study confirms that RP-EBUS-TBLB using a GS without fluoroscopy is a highly safe diagnostic method in patients with PPLs. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy of RP-EBUS-TBLB were 67.8%, 100%, 100%, 52.0%, and 76.1%, respectively. The diagnostic performance of RP-EBUS-TBLB was better in larger PPLs. Larger lesions (Ōēź20 mm), positive bronchus sign in chest CT, a solid lesion, and an EBUS image with the probe within the lesion were independent factors affecting diagnostic success. Pneumothorax occurred in 2.0% of patients, and 0.5% required chest tube insertion. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study to have analyzed the utility of RP-EBUS-TBLB using a GS without fluoroscopy.

Kurimoto et al. [

5] developed a technique for EBUS using a GS, and mentioned that EBUS-GS is a useful method for collecting samples from PPLs even when the lesions are too small to be detectable under fluoroscopy. In PPLs Ōēż20 mm, TBLB with GS showed a higher diagnostic sensitivity than the TBLB without GS for the diagnosis of PPLs [

15]. In addition, fluoroscopy was not helpful to confirm whether the forceps were within the lesion, and the diagnostic yield was the same regardless of the use of fluoroscopy for PPLsŌēż20 mm. Advantages of the GS technique are that it provides access to bronchial lesions for repeated sampling and protects against bleeding from the biopsy site by wedging the GS into the bronchial lumen [

5]. In diagnosing PPLs Ōēż20 mm, the diagnostic yield of our study (using a GS without fluoroscopy) was 54.7%, comparable to other studies using a GS with fluoroscopy [

16-

19]. In our experience, if GS is appropriately used, a high diagnostic rate can be expected if accurate localization and EBUS image findings are achieved, even if fluoroscopy is not used.

Regarding fluoroscopy, it may be combined with TBLB to confirm whether the forceps are within the lesion. Fluoroscopy can be more helpful in performing biopsy at lower lobe lesions with a high probability of re-positioning of GS due to respiration or coughing. As described in the methods section, the lesion was identified with the RP, perform gain on the first three lung tissue samples, re-inserted the RP to ensure that the GS was not re-positioned in the lesion, and then performed an extra biopsy. Using this approach, we addressed the disadvantages of not using fluoroscopy. As a result, the diagnostic success rate of the right lower lobe (78.8%, 119/151) and left lower lobe (78.0%, 71/91) was not different from the rate of other lobes, as shown in

Table 1. It is important to improve the diagnosis of PPLs and reduce radiation exposure during the examination. Fluoroscopy has disadvantages, including excessive radiation exposure for patients and practitioners. In addition, fluoroscopy consumes additional space, manpower, and cost for installing a shield room. Thus, in institutions where fluoroscopy is difficult to use, RP-EBUS-TBLB using a GS without fluoroscopy can be considered as a useful method for diagnosing PPLs.

A few studies have explored the efficacy and safety of RP-EBUS-TBLB using a GS without fluoroscopy for PPLs. Yoshikawa et al. [

10] were the first to publish the outcomes of RP-EBUS-TBLB in 123 PPLs using a GS without fluoroscopy. A total of 61.8% of PPLs were diagnosed, and the diagnostic yield for PPLs >20 mm (75.6%) was higher than PPLs Ōēż20 mm (29.7%). Lesions >2 cm and the location (middle lobe and the lingular segment) of the PPLs were independent predictors of diagnostic success [

10]. It can be estimated that our research is a little superior in terms of diagnostic accuracy. The diagnostic accuracy was significantly different in PPLs smaller than 3 cm. The difference in baseline characteristics of PPLs between two studies may have affected the results. There was no difference in size of PPLs between the two studies. However, positive bronchus sign in chest CT was higher in our study (476 of 607 lesions, 78.5%) compared to the previous study (76 of 123 lesions, 61.8%). The high percentage of solid lesion in our study (87.3%) compared to the previous study (67.0%) may have also affected the diagnostic accuracy. Eberhardt et al. [

11] conducted a randomized trial of multimodality diagnostic arms; in subgroup analyses, a diagnostic yield of 69% was achieved in EBUS-GS without fluoroscopy in 39 PPLs. Minami et al. [

15] reported that the diagnostic sensitivity of 60 PPLs with EBUS-GS was 83.3%. Minezawa et al. [

12] analyzed 149 PPLs who underwent EBUS-GS without fluoroscopy for small PPLs (Ōēż30 mm) and a total diagnostic yield of 72.5% was reported. CT bronchus sign positive was an independent factor associated with diagnostic success. Zhu et al. [

13] reported diagnosis rate of 64.0% for EBUS-GS without fluoroscopy among 150 PPLs. Our study analyzed 607 PPLs and the diagnostic accuracy was 76.1%. As reported in previous studies, lesions Ōēź20 mm, positive bronchus sign in chest CT, a solid lesion, and EBUS probe within the lesion were independent factors of diagnostic success.

Complication rates of RP-EBUS-TBLB were low in previous studies and most of the complications were small pneumothorax and minimal bleeding problems. One meta-analysis revealed that the overall complications were 2.8%, and chest tube insertion was required in 0.2% of cases [

2]. One observational study focusing on complications of RP-EBUS-TBLB in 965 PPLs showed overall complication rates of 1.3%. Pneumothorax occurred in 0.8% of patients, and 0.3% of the patients required chest tube drainage [

20]. Our study demonstrated that pneumothorax occurred in 12 patients (2.0%) and chest tube insertion was required in three patients (0.5%). The relatively high incidence of pneumothorax compared to other studies is thought to be due to the high proportion of COPD patients (27.8%). Indeed, all three patients who required chest tube insertion were COPD patients with emphysema.

This study had several limitations. First, since it was a retrospective study conducted at a single center with PPLs, the results cannot be generalized, and selection bias cannot be excluded. However, the pulmonologists performed RP-EBUS as a first-choice biopsy modality in their everyday routine practice, not just in selected patients. Second, although our patients were followed-up for at least 12 months, there were 56 patients who still had nodules with an indefinite diagnosis. Although most previously published articles in the fields of RP-EBUS excluded PPLs with an indefinite diagnosis to calculate diagnostic yield, our study included indefinite diagnosis cases in the calculation of diagnostic yield. Given the high diagnostic yield of RP-EBUS-TBLB with GS without fluoroscopy and the acceptable rates of complications, our study showed that it can be performed in routine clinical settings for diagnosing PPLs without fluoroscopy. Moreover, our results highlighted the important role of RP-EBUS in diagnosing PPLs, which required early diagnosis.

In conclusion, RP-EBUS-TBLB using a GS without fluoroscopy is a highly accurate diagnostic method without exposure to radiation and with acceptable complication rates for diagnosing PPLs. Lesions Ōēź20 mm, positive bronchus sign in chest CT, a solid lesion, and having the probe within the lesion were important for diagnostic success.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Print

Print Download Citation

Download Citation