Revised Korean Cough Guidelines, 2020: Recommendations and Summary Statements

Article information

Abstract

Cough is the most common respiratory symptom that can have various causes. It is a major clinical problem that can reduce a patient’s quality of life. Thus, clinical guidelines for the treatment of cough were established in 2014 by the cough guideline committee under the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. From October 2018 to July 2020, cough guidelines were revised by members of the committee based on the first guidelines. The purpose of these guidelines is to help clinicians efficiently diagnose and treat patients with cough. This article highlights the recommendations and summary of the revised Korean cough guidelines. It includes a revised algorithm for the evaluation of acute, subacute, and chronic cough. For a chronic cough, upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), cough variant asthma (CVA), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) should be considered in differential diagnoses. If UACS is suspected, first-generation antihistamines and nasal decongestants can be used empirically. In cases with CVA, inhaled corticosteroids are recommended to improve cough. In patients with suspected chronic cough due to symptomatic GERD, proton pump inhibitors are recommended. Chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis, lung cancer, aspiration, intake of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, intake of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, habitual cough, psychogenic cough, interstitial lung disease, environmental and occupational factors, tuberculosis, obstructive sleep apnea, peritoneal dialysis, and unexplained cough can also be considered as causes of a chronic cough. Chronic cough due to laryngeal dysfunction syndrome has been newly added to the guidelines.

Introduction

Cough is the most common respiratory symptom that can have various causes [1]. It is a major clinical problem that can reduce a patient’s quality of life [2]. Thus, clinical guidelines for the treatment of cough were established in 2014 by the cough guideline committee under the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. The first guidelines for cough proposed recommendations for objective and standardized diagnostic and treatment practices. It was based on a systematic literature review of domestic and international clinical studies on cough, with high degrees of evidence and strength of recommendation.

From October 2018 to July 2020, the cough guidelines were revised by members of the cough guideline committee. The purpose of these guidelines is to help clinicians efficiently diagnose and treat patients with a cough. The revised guidelines include epidemiological data on chronic cough in Korea provided by the cough guideline committee, the Cough Assessment Test (COAT) as a noble assessment tool for cough, contents of the revised American College of Chest Physicians and European Respiratory Society guidelines, and results of Korean studies based on the first cough guidelines. Contents of these guidelines are confined to only adult patients. The 2020 revision of the Korean cough guidelines was written in the Korean language and published in December 2020. In this article, we present a summary of the revised Korean cough guidelines, 2020 with recommendations.

1. Definition, mechanism, and epidemiology of cough

2. Classification of cough

3. Tools for assessment of cough

1) Recommendation

– COAT [6] is recommended to assess various effects of cough in a standardized manner (evidence, moderate; recommendation, strong).

4. Acute and subacute cough

1) Recommendation

– If a patient with an acute cough has any warning signs (Table 1), chest X-rays are necessary regardless of the duration of cough.

– Empirical antibiotic therapy for cough due to an acute bronchitis can be considered only in patients with purulent sputum (evidence, low; recommendation, strong).

– In patients with acute and subacute cough, beta-2 agonists should not be used to improve cough symptoms (evidence, low; recommendation, strong) [9].

2) Summary

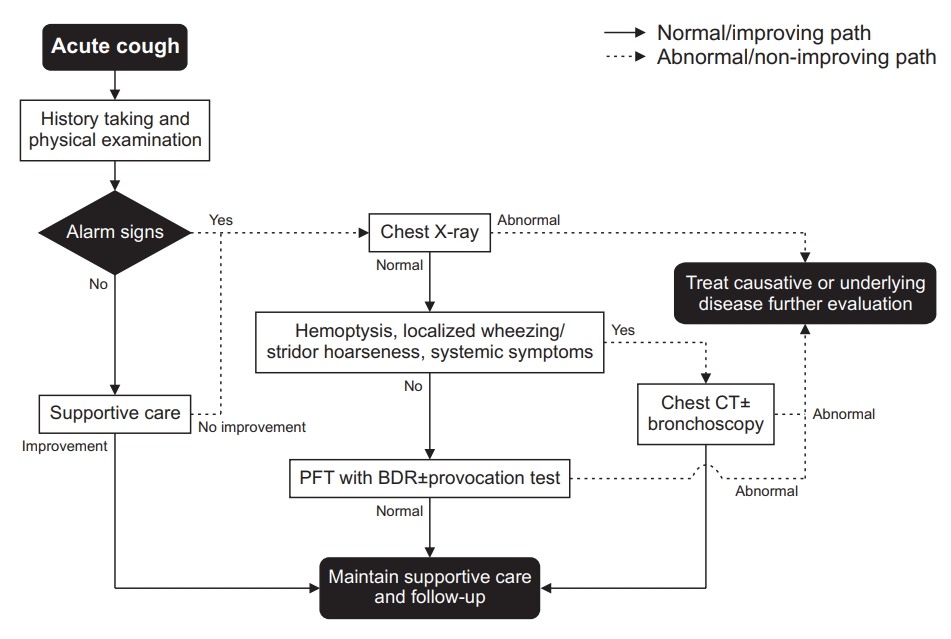

– Acute cough is defined as a cough lasting no more than 3 weeks. Upper respiratory infections and acute bronchitis caused by respiratory viruses are the most common causes [10] (Figure 1).

Algorithm for the evaluation of an acute cough. BDR: bronchodilator response; CT: computed tomography; PFT: pulmonary function test.

– In patients with acute cough without any warning signs (Table 1), symptomatic therapy is first administered before any investigations.

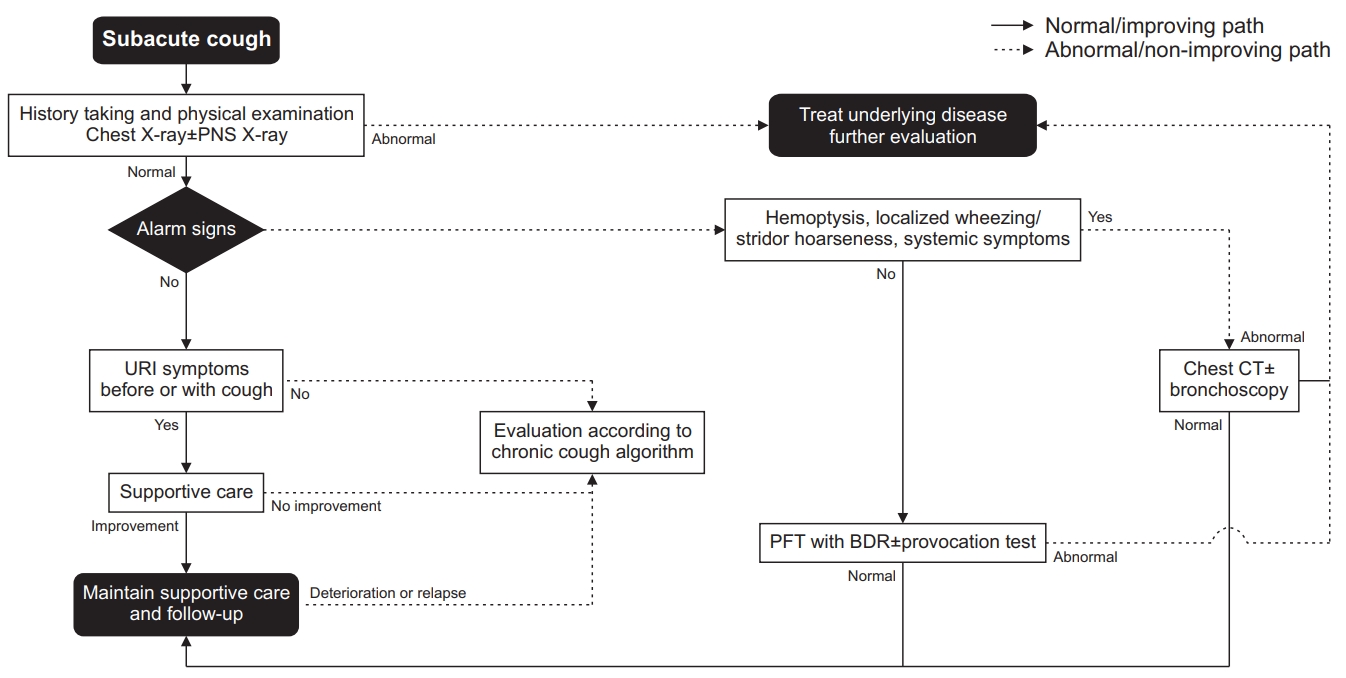

– Subacute cough is defined as a cough lasting 3 weeks to 8 weeks. History taking, physical examination, and chest radiography are recommended (Figure 2).

Algorithm for the evaluation of subacute cough. BDR: bronchodilator response; CT: computed tomography; PFT: pulmonary function test; PNS: paranasal sinus; URI: upper respiratory infection.

– Post-infectious cough is the most common cause of subacute cough. It is often associated with viral infections. Symptomatic treatment without antibiotics can improve the cough [11].

– Antibiotics therapy can be effective in treating subacute cough due to bacterial infections.

5. Chronic cough

1) Summary

– Chronic cough is defined as a cough lasting for more than 8 weeks.

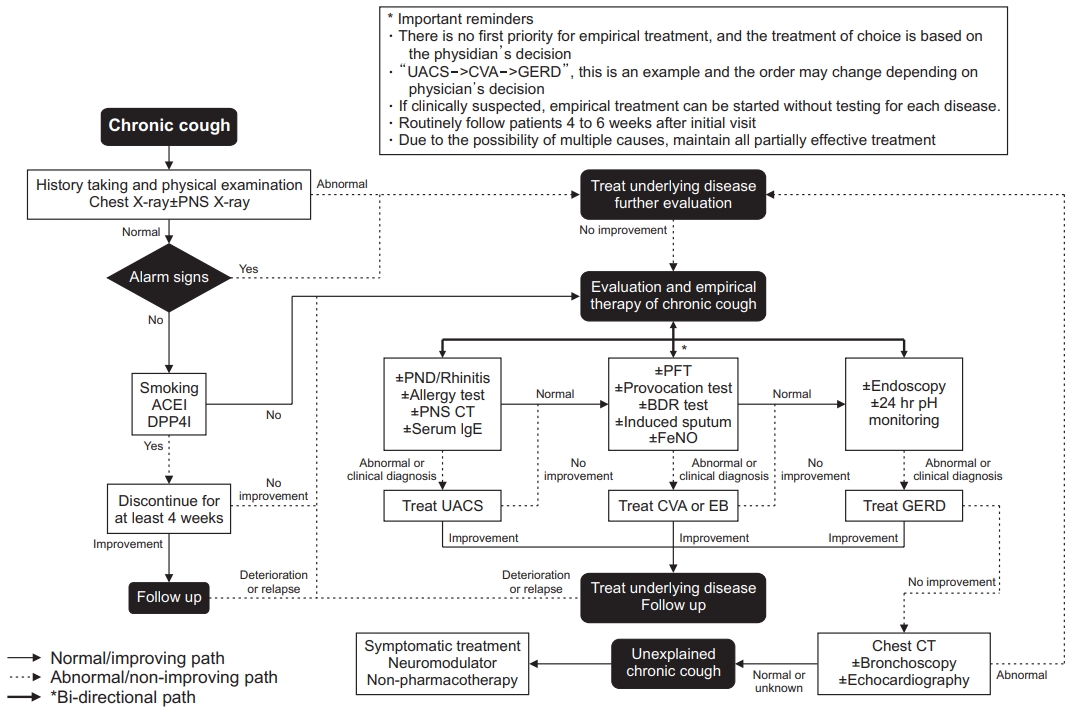

– History taking, including details of smoking habits, accompanying symptoms, and medication, is helpful for differential diagnosis. Clinicians should take it first and enough (Figure 3).

Algorithm for the evaluation of chronic cough. ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BDR: bronchodilator response; CT: computed tomography; CVA: cough variant asthma; DPP4I: dipeptidylpeptidase-4 inhibitor; EB: eosinophilic bronchitis; FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; PFT: pulmonary function test; PND: postnasal drip; PNS: paranasal sinus; UACS: upper airway cough syndrome.

– Tests for upper airway cough syndrome (UACS), cough variant asthma (CVA), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

– Chest radiography should be performed first [12-15]. Other tests can be performed in a step-wise manner based on symptoms of the patient and facilities of the hospital.

6. Upper airway cough syndrome

1) Recommendation

– In UACS, intranasal steroids can be used to improve cough (evidence, very low; recommendation, weak).

– In UACS, oral antihistamines are recommended to improve cough (evidence, very low; recommendation, strong).

– In UACS, only using nasal decongestant is not recommended to improve cough (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, strong).

– In UACS, intranasal antihistamine is not considered effective in improving cough (evidence, very low; recommendation, weak).

– In UACS, antibiotics are not recommended to improve cough (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, strong).

2) Summary

– UACS is a syndrome in which various upper airway diseases can cause a cough [16,17].

– It is diagnosed based on symptoms, physical examination, radiologic findings, and response to an empirical treatment [18,19].

– If UACS is diagnosed, adequate treatment should be initiated.

– If UACS is suspected, first-generation antihistamine and nasal decongestants can be used empirically.

7. Cough variant asthma

1) Recommendation

– In patients with CVA, non-invasive measurement of airway inflammation such as sputum eosinophil counts and fractional exhaled nitric oxide should be considered (evidence, moderate; recommendation, weak) [20].

– In CVA, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are recommended to improve cough. If the cough is not well controlled with ICS, the dose of ICS may be increased and/or a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) or a long-acting bronchodilator may be added (evidence, moderate; recommendation, strong).

8. Eosinophilic bronchitis (EB)

1) Recommendation

– In EB, ICS is recommended to improve cough (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, strong).

– In EB, LTRA is not recommended to improve cough (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, strong).

9. Gastroesophageal reflex disease

1) Recommendation

– In patients with suspected chronic cough due to symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux, proton pump inhibitors are recommended to improve the cough (evidence, low; recommendation, weak).

2) Summary

– In patients with suspected chronic cough due to a refluxcough syndrome, we recommend the following treatment: (1) diet modification to promote weight loss in patients who are overweight or obese; (2) head of bed elevation [24] and avoiding meals within 3 hours of bedtime [25].

– In patients who report heartburn and regurgitation, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), H2-receptor antagonists, alginate, and antacid therapy are sufficient to control these symptoms.

– In patients with suspected chronic cough due to refluxcough syndrome without heartburn or regurgitation, using PPI therapy alone is not recommended [26,27].

10. Chronic bronchitis

1) Recommendation

– Smoking cessation is recommended to improve cough in patients with chronic bronchitis (CB) (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, strong).

– In CB, mucoactive agents can be considered to improve the cough (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, weak).

2) Summary

– Treatment for CB with decreased lung function should follow chronic obstructive pulmonary disease guidelines.

– Smoking cessation is the most effective treatment for CB with a decreased lung function [28,29].

– CB is the most common cause of cough in smokers [30].

– Mucoactive agents are effective in improving cough in CB with a decreased lung function [31].

– Inhaled short-acting beta-agonist (SABA), theophylline, ICS/long-acting beta-agonist, and codeine can be used to treat cough in CB with a decreased lung function [32].

11. Bronchiectasis

1) Summary

– When bronchiectasis is suspected, high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is necessary even if chest X-ray is normal [33].

– Long-term antibiotic treatment should be cautiously considered because it can control acute exacerbation caused by infection. However, it can also lead to adverse effects [33-37].

12. Bronchiolitis

1) Recommendation

– In diffuse panbronchiolitis, low-dose macrolide antibiotics are recommended to improve cough (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, strong).

2) Summary

– Bronchiolitis should be preferentially considered when there are irreversible airflow obstruction, suspicion of small airway disease on HRCT, and purulent sputa in patients with a chronic cough [38].

13. Lung cancer

1) Summary

– Chest X-ray should be performed in patients who have risk factors for lung cancer or metastatic lung cancer [39].

– Bronchoscopy and chest CT should be performed when endobronchial invasion by the tumor is suspected even if chest X-ray is normal [39].

– In patients with lung cancer, the reason for cough might not be cancer. Thus, further evaluation is necessary [40].

– In patients with lung cancer, cough should be actively managed because it can affect their quality of life and prognosis [41].

– In patients with lung cancer, stepwise treatment based on the mechanism of the drug should be considered to control their cough [42].

14. Aspiration

1) Summary

– Oropharyngeal dysphagia and aspiration should be checked in cases of cough during eating or swallowing food [43].

15. Drug-induced cough

1) Recommendation

– Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and dipeptidylpeptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4I) should be considered as causes of chronic cough. Cessation of these drugs is recommended to control the cough (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, strong).

2) Summary

– The mechanism of drug-induced cough is the accumulation of bradykinin in the upper respiratory tract [44,45]. ACEI and DPP4I are representative drugs that can cause a chronic cough.

– To diagnose cough due to drugs, a detailed history taking including ACEI or DPP4I intake is necessary.

– Usually, the cough subsides 1–4 weeks after cessation of these drugs. However, it can last for more than 3 months in some patients [46-49].

16. Habitual and psychogenic cough

1) Summary

– Habitual and psychogenic cough is an unconsciously persistent cough without an underlying disease. It can be considered when there is no obvious reason for the cough, or when cough does not respond to a conventional therapy [50,51].

– Habitual and psychogenic cough usually develops during childhood and adolescence. When it develops in adults, it might be accompanied by psychological conditions [52].

– Habitual and psychogenic cough is characterized by aggravation during emotional stress, social activity, and disappearance during sleep. However, the presence or absence of these characteristics should not be used to diagnose or exclude a psychogenic cough [53-55].

– Habitual and psychogenic cough can be diagnosed only when other causes are ruled out [52].

– Psychological consultation and therapy can be considered [54,56].

17. Interstitial lung disease

1) Recommendation

– For patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) who present with a troublesome cough, patients should be assessed for progression of their underlying ILD or complications from immunosuppressive treatment (e.g., adverse effects of drugs, pulmonary infection). They should also be considered for further investigation/treatment trials for their cough according to guidelines for acute, subacute, and chronic cough [57].

– If alternative treatments have failed in a patient with a chronic cough due to ILD and the cough adversely affects the patient’s quality of life, opiates can be used for symptom control in a palliative care setting with reassessment of the benefits and risks after one week and then monthly before continuing [57].

2) Summary

– Chronic cough is a common symptom of ILD [57].

– ILD should be included in the differential diagnosis of a chronic cough since chest X-ray can be normal in 5%–10% of patients with early ILD.

– Progression of cough can vary according to the cause and underlying disease.

18. Cough due to environmental and occupational factors

1) Recommendation

– For every adult patient with a chronic cough, occupational and environmental causes should be routinely elicited in history taking.

– For a patient with a chronic cough, if the history suggests an occupational or environmental association, it be confirmed by objective testing if possible [58].

2) Summary

– For an adult patient with a chronic cough and an occupational or environmental exposure history, appropriate objective tests should be performed to elucidate potential mechanistic associations between cough and the suspected exposure [58], including the following:

ㆍMethacholine challenge for cough associated with work-related asthma/eosinophilic bronchitis

ㆍSputum/induced sputum cytology for eosinophilia

ㆍBefore and after exposure tests to demonstrate the potential causality (e.g., perform both at the end of a regular working week and, if positive, repeat at the end of a period off work such as the end of vacation, to document any work-related changes).

ㆍImmunologic tests for hypersensitivity guided by the specific exposure history including:

◦Skin tests

◦Specific serum IgE antibodies

◦Specific serum IgG antibodies for suspected hypersensitivity pneumonitis

◦Beryllium lymphocyte proliferation tests for chronic beryllium disease

– Environmental and occupational factors can evoke cough in themselves or can aggravate cough due to other causes. Thus, consideration of environmental and occupational factors is mandatory [58].

– Detailed history taking of exposure and occupation is important to identify environmental and occupational factors [58].

19. Cough due to tuberculosis and other infections

1) Recommendation

– Considering the prevalence of tuberculosis (TB) in Korea, active TB should be suspected and evaluated for cough lasting for more than 2 weeks.

20. Obstructive sleep apnea

21. Cough and peritoneal dialysis

22. Cough in immunocompromised patients

23. Uncommon causes of cough

1) Recommendation

– In patients with chronic cough, uncommon causes should be considered when cough persists after evaluating common causes and when the diagnostic evaluation suggests that an uncommon cause, pulmonary or extrapulmonary, is the contributing factor [71].

2) Summary

– In the diagnosis of uncommon causes of cough, knowledge of the disease, clinical suspicion, and adequate evaluation are very important [72].

– If cough persists after ruling out the most common causes, a CT scan should be performed. If necessary, a bronchoscopic evaluation should be perfomed [71].

– In patients who present with an abrupt onset of cough, the possibility of a foreign body in the airway should be considered.

24. Idiopathic cough (unexplained chronic cough)

1) Recommendation

– In an idiopathic cough, an antitussive can be considered to improve the cough (evidence, expert opinion; recommendation, weak) [73].

25. Laryngeal dysfunction syndrome

1) Recommendation

– In patients with a laryngeal dysfunction syndrome, multicomponent speech therapy is recommended to improve the cough.

– In patients with a laryngeal dysfunction syndrome, gabapentin, oral morphine, pregabalin, or amitriptyline is recommended to improve the cough.

– In patients with laryngeal dysfunction syndrome, local injection of botulinum toxin is recommended to improve the cough.

2) Summary

– Laryngeal dysfunction syndrome is a cough caused by innocuous or mildly unpleasant stimuli due to laryngeal hypersensitivity and laryngeal dysfunction. It is considered as one of the causes of a chronic refractory cough [74-76].

– Laryngeal dysfunction syndrome is diagnosed based on clinical features and laryngoscopic findings [77].

– Speech therapy has long been considered as the mainstay of treatment for laryngeal dysfunction syndrome.

– Pharmacotherapy and local injection of botulinum toxin can be considered to improve the cough [78].

26. Treatment agents for cough: antitussive and mucoactive agent

1) Summary

– Antitussives are classified as central and peripheral [79,80].

ㆍNarcotic central antitussive: morphine, codeine

ㆍNonopioid central antitussive: dextromethorphan, levopropoxyphene

ㆍPeripheral antitussive: benzonatate, benproperine, theobromine

– Mucoactive agents can be classified as expectorants, mucoregulatory agents, mucolytics, and mucokinetics [81,82].

ㆍExpectorants: hypertonic saline, iodinated glycerol, domiodol, guaifenesin, and ion channel modifiers

ㆍMucoregulatory agents: carbocysteine, anticholinergics, glucocorticoids, and macrolide antibiotics

ㆍMucolytics

◦Classic mucolytics: N-acetylcysteine, N-acetylin, bromhexine, erdosteine, and fudosteine

◦Peptide mucolytics: dornase alpha, gelsolin, and thymosin β4

◦Nondestructive mucolytics: dextran and heparin

ㆍMucokinetics: inhaled SABA, methylxanthine, surfactant, ambroxol, and acebrophylline

– Newly evaluated drugs include gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, and gefapixant (P2X3 receptor antagonist).

Notes

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: Kim JW, Kim DG, Kim HJ. Methodology: Kim DK, Shin JW, Yoon HK, Jang SH. Formal analysis: Min KH, Kim YH, Kim SK. Data curation: Jeong I, Kim JH, Lee SW. Software: Joo H. Validation: Kim CY, Park SY. Investigation: Choi H, Yoo H. Writing - original draft preparation: Joo H. Writing - review and editing: Koo HK, Moon JY, An TJ, Rhee CK. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

No funding to declare.