Economic Burden of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review

Article information

Abstract

Globally, providing evidence on the economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is becoming essential as it assists the health authorities to efficiently allocate resources. This study aimed to summarize the literature on economic burden evidence for COPD from 1990 to 2019. This study examined the economic burden of COPD through a systematic review of studies from 1990 to 2019. A search was done in online databases, including Web of Science, PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. After screening 12,734 studies, 43 articles that met the inclusion criteria were identified. General study information and data on direct, indirect, and intangible costs were extracted and converted to 2018 international dollars (Int$). Findings revealed that the total direct costs ranged from Int$ 52.08 (India) to Int$ 13,776.33 (Canada) across 16 studies, with drug costs rannging from Int$ 70.07 (Vietnam) to Int$ 8,706.9 (China) in 11 studies. Eight studies explored indirect costs, while one highlighted caregivers’ direct costs at approximately Int$ 1,207.8 (Greece). This study underscores the limited research on COPD caregivers’ economic burdens, particularly in developing countries, emphasizing the importance of increased research support, particularly in high-resource settings. This study provides information about the demographics and economic burden of COPD from 1990 to 2019. More strategies to reduce the frequency of hospital admissions and acute care services should be implemented to improve the quality of COPD patients’ lives and reduce the disease’s rising economic burden.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was ranked as the third highest contributor to global mortality in 2019, accounting for 3.23 million fatalities. Additionally, COPD held the seventh position among the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years lost worldwide [1]. In 2017, it was estimated that more than 300 million people were living with COPD worldwide, of which the major contributors were low- and middle-income countries [2]. Annually, COPD causes more than three million deaths globally [3]. In developed countries, the cost of COPD is estimated to range from 1,030 billion in 2010 to 2,200 billion US dollars (USD) in 2030, while in developing countries the cost is projected to be USD 2,600 billion in 2030. The cost of illness per person living with COPD will reach USD 4,800 in 2030 [4]. Additionally, approximately 10% of global productivity losses have been attributable to COPD, and this loss could equate to USD 6,700 per COPD patient [5].

The costs of COPD treatment and care are burdensome. Previous literature recorded a high rate of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) among people with COPD [6,7]. A study in Australia observed that 46% of participants shared CHE [8]. This exceptionally high incidence of CHEs is likely due to the significant out-of-pocket payment for COPD treatment. Some studies indicated that COPD treatment cost (USD 236.2) [9] was superior to other severe non-communicable conditions such as mental health (USD 215) [10] and ischemic heart disease (USD 78) [11]. The average treatment cost of COPD increased from USD 6,300 in 2004 to USD 9,545 in 2010 [3]. Hospitalization is the major cost component. The mean cost of hospitalization exceeds USD 3,500, with medical expenses making up the majority (over 45.3% [USD 1,500]) [3]. Diagnosis and general medical expenses follow, totaling to more than USD 900 and USD 400, respectively [3]. In addition, a study in Greece showed that one-third of patients relied on support from family, relatives, or a supportive environment for daily activities, accounting for about 3.6 hours per day, across 4.1 days per week, of unpaid caregivers’ time [12].

Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses of intervention and treatment provided appropriate evidence for clinical practice and policy development [13]. These studies collected available empirical research evidence to answer research questions regarding the treatments and interventions for COPD [14-16]. Although there is existing evidence concerning the economic implications of COPD, it predominantly consists of individual studies that are constrained by variables such as focusing only on a single nation [17,18], providing a concise overview of the economic impact of COPD [19], and conducting 10 years and drawing data from three databases [19]. Further rigorous investigation is warranted to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the current COPD burden in settings adhering to globally recognized treatment guidelines, such as those outlined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). This review used studies from four databases to validate the COPD economic burden worldwide, providing direct, indirect, and intangible costs of COPD.

In conclusion, this study aimed to provide evidence on the burden of COPD, which is becoming globally urgent. Our results might help health authorities improve resource allocation and encourage people to have an adequate lifestyle [20].

Materials and Methods

This systematic review included studies on the economic burden of COPD in the period 1990 to 2019.

1. Eligible criteria

1) Inclusion criteria

We applied the Population–Indicator–Outcomes–Study types (PIO-S) question structure to develop an inclusion criteria and search strategy for articles as follows:

(1) Population (P): People with a diagnosis and treatment for COPD or who are the caregivers of COPD patients.

(2) Indicator (I): Studies mentioned patient characteristics, COPD symptoms, and treatment type.

(3) Outcomes (O): The economic burden among studies’ subjects:

ㆍ Direct cost is the cost of resources used direction for patient care: drugs or staff.

ㆍ Indirect cost is the expenses that cannot be directly attributed to a single, specific final cost objective. Rather, these costs are related to multiple final cost objectives or serve an intermediate cost objective (production loss, transportation).

ㆍ Intangible costs are indicators that cannot be measured or quantified. Therefore, in this study, intangible cost refers to pain, suffering, social stigma, and patient quality of life change.

(4) Study types (S): Every type of preliminary study, cross-sectional, case-control, and appropriate waves of longitudinal studies, and randomized clinical trials, were eligible for inclusion.

(5) The papers of our choice were research articles and research reviews in English.

(6) Period of included research articles was 1990 to 2019.

2) Exclusion criteria

(1) Research study is not written in English.

(2) Systematic review and meta-analysis studies.

2. Selection of studies and data extraction

The data selection was as follows:

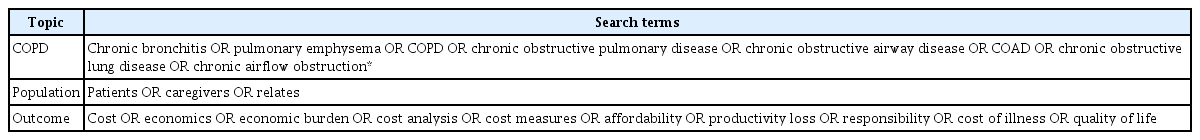

Step 1: The following keywords were chosen based on the experts’ recommendations in the field and previous studies. The “search terms” were combined with Boolean operators “AND” to connect keywords related to COPD, population, and economic cost (Table 1).

Step 2: Web of Science, PubMed/Medline, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library were used to download the papers. Two researchers downloaded the data independently to ensure accuracy.

Step 3: The results were exported to Endnote 7 and duplicate records were removed. After that, the papers’ titles and abstracts were examined to see if they satisfied the eligibility criteria based on the structured PIO-S questions. Studies that were unrelated to the study’s goal were omitted. The full texts of studies that satisfied the selection criteria were downloaded.

Step 4: Two reviewers piloted a data extraction form, which was then used for all investigations. Each review author separately extracted: (1) author-date; (2) study design; (3) participant description; (4) sample size; (5) follow-up period; (6) outcomes; (7) study findings; and (8) quality evaluation. The data extraction results of the two reviewers were reviewed to ensure reliability and discrepancies were solved through discussion.

3. Data analysis

Two reviewers extracted direct and indirect costs data from the dataset. After that, purchasing power parities (PPPs) data was downloaded from the World Bank website (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD). PPPs represent currency conversion rates aimed at equalizing the purchasing power of diverse currencies by adjusting for variations in price levels among countries [21]. For comparative analysis, we gathered PPP data for the year 2018 to convert all costs into international data.

In this study, we also evaluated the burden and changes in the quality of life among COPD patients reported in the previous studies, which used the scales for the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD (SGRQ-C), and Caregiver Burden Questionnaire. CAT is a numerical scale questionnaire consisting of eight statements. It assesses various aspects by prompting respondents to assign a score from 0 to 5 for each of the eight areas. A score of 0 signifies no impairment in the respective area, while a score of 5 indicates severe impairment. The overall score, ranging from 0 to 40, reflects the extent to which COPD affects one’s overall health and well-being, with higher scores indicating a more significant impact [22]. The SGRQ-C is a condensed iteration of the SGRQ, crafted through the thorough analysis of extensive data from sizable studies in COPD. Since it is specifically designed using COPD data, the SGRQ-C is considered valid for assessing COPD. While its applicability to other conditions has not been formally established, it is expected to exhibit performance similar to the comprehensive SGRQ-C [23]. The Caregiver Burden Scale, developed by Elmstahl et al. [24] in 1996, is a 22-item questionnaire designed to assess the subjective burden experienced by caregivers across five domains: general strain, isolation, disappointment, emotional involvement, and environment. Respondents express the frequency with which each item applies to them using a 4-point scale, ranging from “not at all” to “often” [24].

The study applied the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to illustrate the search and screening flow.

Figure 1 indicates the screening process and the decisions taken during study selection. Initially, 12,734 documents were determined as relevant. After deduplication (n=3,848) and exclusion through screening the title and abstract (n=612), 342 records remained. Finally, out of the 342 studies, only 43 articles met the inclusion criteria.

Results

1. Study characteristics

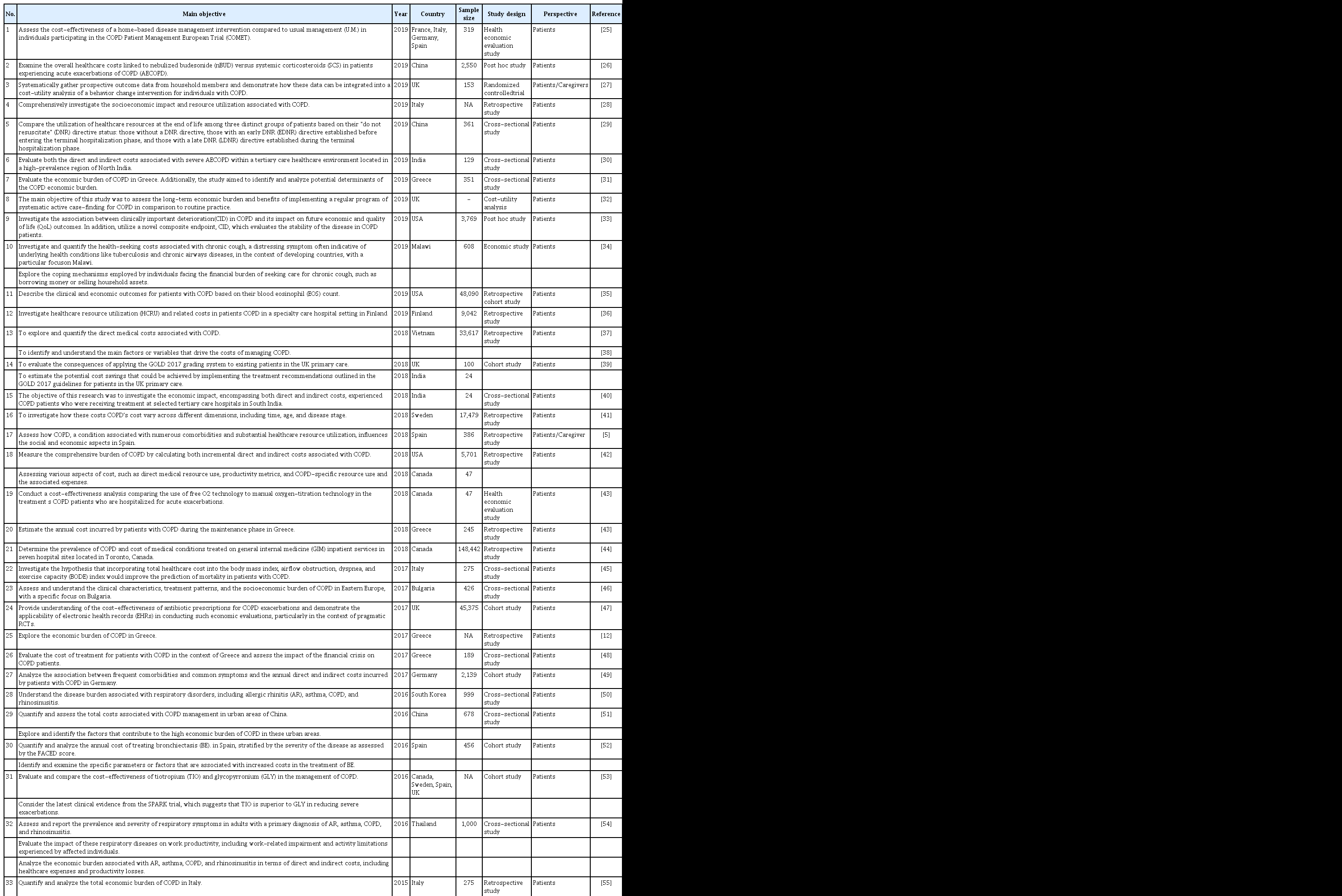

A total of 43 studies met the inclusion criteria. Table 2 shows the descriptive characteristics of all the selected articles [5,12,25-65]. The main target populations were people living with COPD and caregivers. The majority of studies were conducted in developed countries: the USA (nine studies), followed by the United Kingdom (six studies), Italy (five studies), and Spain (five studies). The most common study design was retrospective study design (18 studies), followed by a cross-sectional study design (12 studies), and a cohort study design (six studies).

2. Direct cost

Total cost (10 studies), drug costs (10 studies), and nonmedical costs (three studies) were among the 16 reported direct costs. All the costs in Table 3 have been converted to international dollars (Int$; year 2018) [28-32,39-42,44,51,55,62,66,67]. The total direct cost, total medical direct cost, pharmaceutical therapy cost, outpatient cost, and total nonmedical cost were calculated. The total direct costs ranged from Int$ 1,098 (UK) to Int$ 43,994 (India). In terms of components of the nonmedical direct cost, we discovered differences between studies. There were also cost-effectiveness studies; therefore, there were differences in treatment techniques [26,47]. Results showed that, direct costs are much higher in developed countries than in developing countries. Hospital stays, medicine prices, and treatment expenses contribute to most of the direct costs. Nonmedical costs are typically low but can be higher in impoverished countries. The cost of immediate treatment varies substantially depending on the type and model of treatment. Notably, while the procedures might be the same, their efficiency may vary depending on the features of the health system and the resources available in each country. Indeed, the economic burden of COPD significantly differs depending on a country’s specific circumstances, including factors such as average income, access to health insurance, and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

3. Indirect cost

Table 4 described the indirect cost of COPD in ITN$. Nine studies reported indirect costs [5,12,28,30,31,41,51,55,67]. The survey of Kourlaba et al. [31] reported the most details when the study used the CAT score, modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) breathless scale, and GOLD for categories. The indirect cost ranged from Int$ 33.0 to ITN$ 3,265.3. Significant differences existed between levels in each scale and among the three scales. Dal Negro et al. [55] found out that there was no significant difference in total indirect cost between male and female patients. According to Souliotis et al. [12], over 33% of patients received daily assistance from family, friends, and a friendly environment, consuming 3.6 hours per day, 4.1 days per week, and accounting for Int$ 1,207.8 of nonpaid caregivers’ time and money.

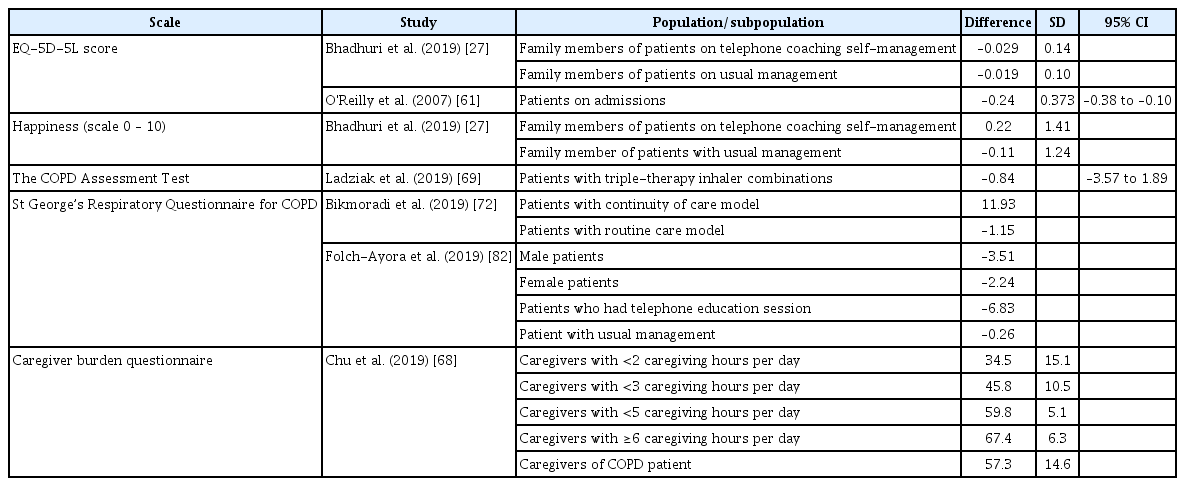

4. Intangible cost

Intangible costs are the unquantifiable impacts of an identifiable cause, such as pain, joy, or physical limitations, which can impact total productive performance. Intangible costs in this study were assessed using the patients’ and relatives’ variation of biopsychosocial quality of life after the diagnosis; quality of life in this context includes physical health, social contacts, and emotional health (Table 5). The research synthesizes six studies on the intangible cost in patients and caregivers. On all scales, the quality of life was reduced compared to before and after diagnosis. The caregiver’s burden increases as the time to care for the patient increases [68].

In Table 5, various health-related measures and their impact on individuals’ well-being are presented across different studies. The EuroQol 5-dimension 5-level (EQ5D-5L) scores show a slight decrease for family members of patients undergoing telephone coaching self-management compared to usual management [27,61]. Happiness scores, on a scale of 0 to 10, indicated a positive change for those in telephone coaching self-management but a decrease for those in usual management [27]. The CAT indicated an improvement in scores for patients using the modified inhaler combinations. However, it is noteworthy that this improvement was not statistically significant (95% confidence interval [CI], –3.57 to 1.89; p=0.525) [69].

The SGRQ-C highlights diverse impacts on quality of life, with different scores for continuity of care and routine care models and variations based on gender, education sections, and management types [70,71]. Lastly, the Caregiver Burden Questionnaire reveals increasing burden scores for caregivers with higher daily caregiving hours and those caring for COPD patients [68]. These findings provide insights into the multidimensional aspects of health and well-being in the context of COPD and its management.

Discussion

This study provided evidence of the economic burden and factors associated with the cost of COPD from 1990 to 2019. The outpatient visits and pharmaceutical therapy costs were the highest direct costs; meanwhile, the indirect costs were less researched. The findings of this study confirmed little research on economic burdens on caregivers of COPD patients and those conducted in developing countries.

In our dataset, four studies were conducted in lower-middle- and low-income countries [30,34,36,40], and seven for the upper-income countries [26,29,51,72,73]. Similar to results of several previous studies, these findings emphasize the lack of research on the economic costs of COPD in developing countries [26]. Probably due to human resources, finance, and infrastructure limitations in these countries [70]. This phenomenon calls for action from global researchers and the need to cooperate with researchers in high-resource settings.

The findings show that the most significant direct costs related to COPD were outpatient visits and pharmaceutical therapy costs [31,35,71]. As the disease worsens, patients need to spend more on palliative care, life maintenance, and hospital stay, which leads to an increase in the cost of hospitalization [58,74]. Other healthcare resources might contribute to COPD’s direct costs, such as home oxygen therapy and physician or specialist home visits [32,33]. In our dataset, no studies mentioned catastrophic costs due to COPD. However, the annual increase in COPD’s cost and long-term treatment characteristics could lead to a long-term economic burden on COPD patients.

Regarding indirect cost, our study included several dimensions of workforce participation, for instance, work and wage loss of COPD patients and caregivers, limitation, and disability in activities [75]. In our dataset, one study mentioned caregiver’s indirect cost [12]. Some studies also show that indirect costs can sometimes account for approximately 10% of the total economic burden [12,56]. However, the indirect cost of COPD is more challenging to control than the direct cost due to the various analytical components in indirect cost measurement [76]. The method of calculating the indirect cost burden is inconsistent among countries due to the different determinations of the workday value.

The study results indicate that the studies on the economic burden on caregivers of COPD patients are limited. Five studies in our dataset mentioned theme focusing on quality of life, the amount of time that caregivers spend for caring, family caregivers psychology, and burden [27,41,68,77,78]. Besides, there has been a lack of studies on mental or physical health of family caregivers’ of COPD patients.

This research found a link between the more significant reported burden of COPD (breathlessness, symptoms, and comorbidities) and higher overall societal expenses per patient [26,59,77,78]. Thus, the severity of the disease and symptoms might be one of the factors that influence the economic burden of COPD.

Health risk behaviors such as alcohol consumption have been proven to increase cross-reinforcement among COPD patients who struggle to achieve smoking cessation [79]. Regarding insurance and economic factors, developing countries have a wide range of community-based health insurance schemes and every insurance scheme aims to protect the vulnerable people in the system by sharing risk [80].

Finally, the management of the severity and symptoms of COPD is critical. Under well-controlled circumstances, the patient’s symptoms and health effects are slow and not frantic. However, when patients progress to exacerbation of COPD, their lives may be affected immediately. Preventing exacerbation in people with COPD can help them live healthier lives and reduce the risk of death [81]. Models of monitoring and telemedicine care, home-based models, and utilizing local primary care facilities are effective treatment and palliative care methods for COPD patients [27,69,78,82]. Our study found out that there have been valuable categorization methods in providing appropriate services to patients, such as GOLD, mMRC breathless scale, and CAT limiting the economic burden of COPD treatment [31,32,35,36,66]. However, future well-designed studies must compare these options with large populations to reach accurate conclusions.

The findings of this study have several implications. First, due to the insufficient economic burden of research related to caregivers, future research should focus on the characteristics and problems of caregivers. Therefore, suitable public health programs should be implemented to reduce the economic burden and negative impacts on caregivers. Second, there are differences in treatment costs of COPD among smokers, former smokers, and nonsmokers, which suggest the negative effects of smoking on progression COPD. Thus, smoking prevention and cessation programs should be implemented early at schools and universities to prevent high-risk behaviors. In addition, when managing symptoms and severity of COPD, it is essential to raise awareness about COPD and self-management COPD intervention among people. Due to limited financial resources, self-management COPD intervention should be implemented in developing countries such as Vietnam. Further cost-effectiveness research about options, drugs, and treatment models for COPD is required to identify the most optimal guideline for patients and relatives to reduce the economic burden of COPD.

In this study, dome limitations need to be considered. First, only English publications were selected, which restricted our sample. Second, our study focused on the economic burden of COPD with the results having many exact numbers regarding economic cost. Finally, the database was limited to the peer-review papers only. Grey literatures and proceedings were not included, which may effect the results.

In conclusion, our findings highlight the considerable variation in COPD-related costs worldwide. This study confirmed a wide variation in the total direct cost of COPD, a diverse drug cost, and a limited exploration of the indirect cost associated with COPD in different countries. In addition, our findings emphasize the limited research on the economic burdens COPD caregivers face. It advocates for increased research support, especially by high-resource settings. These results highlight the need for more studies to better understand and address the economic aspects of COPD, with a focus on caregivers and diverse global contexts.

Notes

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: Pham HQ, Pham KHT, Ha GH, Nguyen THT. Methodology: Pham HQ, Ha GH, Nguyen THT. Formal analysis: Pham HQ, Ha GH, Nguyen THT. Data curation: Pham TT, Nguyen HT. Writing - original draft preparation: Pham HQ, Ha GH, Nguyen THT. Writing - review and editing: Pham KHT, Oh JK. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This work was supported by the Domestic Master/PhD Scholarship Program of Vingroup Innovation Foundation.

One of the authors, Trang Huyen Thi Nguyen, received funding from the International Cooperation and Education Program (NCCRI·NCCI 52210-52211, 2023) of the National Cancer Center, Korea.